Egyptian Funerary Art

Egyptian funerary art played a vital role in conveying the profound religious beliefs surrounding the afterlife and the journey of the soul beyond death. These artistic creations were deeply intertwined with the conviction that existence extended beyond the physical realm, with death seen as a transitional stage rather than an endpoint.

Through a rich array of aesthetic objects and images, funerary art served multiple purposes. Firstly, it was intended to provide material provisions for the deceased’s journey into the afterlife, ensuring their comfort and status in the divine realm. Secondly, it served as a commemoration of the life and achievements of the tomb owner, capturing their identity and legacy for eternity. Additionally, funerary art depicted the performance of burial rites and rituals, symbolizing the transition from earthly existence to the realm of the gods. Moreover, these artworks created an environment within the tomb that was believed to facilitate the rebirth and rejuvenation of the deceased in the afterlife. Through their intricate symbolism and meticulous craftsmanship, Egyptian funerary art reflected the profound religious convictions and cultural practices surrounding death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt.

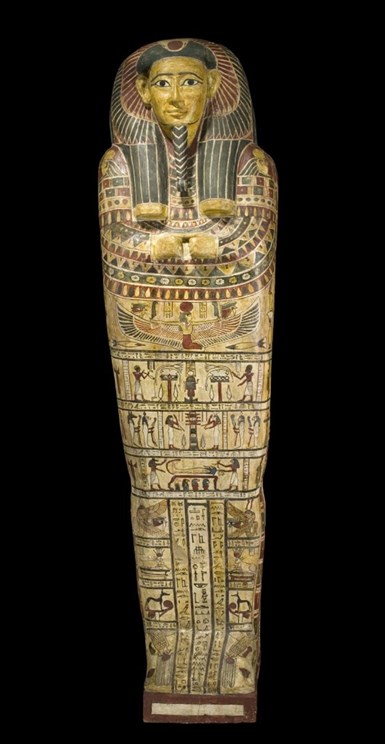

Coffins

The coffin held a profound significance in ancient Egyptian funerary practices, serving as both a protective vessel for the deceased’s physical body and a sacred dwelling place for the eternal essence known as the Ka.

During the Old Kingdom period, a shift occurred, and it became customary once again to lay the body on its side within the coffin. Positioned with the eastern side facing outwards, coffins were adorned with symbolic imagery, including a pair of eyes, enabling the deceased to gaze towards the rising sun—an emblem of daily rejuvenation and rebirth. Externally, coffins were embellished with bands of funerary texts, while internally, depictions of offerings such as food and drink were painted, serving as magical substitutes for the provisions placed within the tomb. Through these intricate decorations and symbols, the coffin not only protected the physical remains of the deceased but also facilitated their journey into the afterlife, ensuring their eternal sustenance and spiritual continuity.

Masks

Funerary masks hold a timeless significance in ancient Egyptian culture, serving as potent symbols of transformation and spiritual elevation. Crafted with exquisite artistry and imbued with sacred symbolism, these masks played a crucial role in guiding the deceased through their journey to the afterlife.

Adorned with intricate designs and precious materials, such as gold and precious stones, Egyptian funerary masks were believed to facilitate the transition from the earthly realm to the divine realm. By donning these masks, the deceased were transformed from mortal beings into immortal spirits, ensuring their eternal connection to the gods and their protection in the realm beyond. In the solemn rituals of death and burial, these masks stood as powerful guardians, preserving the identity and guiding the soul of the departed on its timeless voyage through eternity.

Canopic Jars

During the First Intermediate Period, a significant evolution occurred in the design of canopic jars. Prior to this period, the stoppers of these vessels were typically plain or rudimentary. However, during this transitional phase, artisans began to craft stoppers in the likeness of human heads, marking a departure from earlier conventions.

As Egyptian funerary practices continued to evolve, the design of canopic jar stoppers further evolved during the late 18th Dynasty. At this time, they became more elaborate, often fashioned to resemble the heads of protective genii such as baboons, jackals, falcons, and humans. This intricate symbolism reflected the profound religious beliefs of the ancient Egyptians, as these genii were believed to safeguard the organs contained within the jars, ensuring the preservation and spiritual integrity of the deceased in the afterlife.

Ushabtis

Ushabtis, also known as shabtis or shawabtis, held a crucial role in ancient Egyptian funerary practices, serving as surrogate laborers for the deceased in the afterlife.

These figurines evolved from simple servant statues found among grave goods during the Middle Kingdom period. Initially crafted from materials like wax, clay, or wood, ushabtis later took on the form of mummiform figures, symbolizing the deceased individual. By the end of the 12th Dynasty, ushabtis became standardized and were often inscribed with a specific funerary text known as the “ushabti text.” This text was believed to invoke magical powers, compelling the ushabti to fulfill any labor required of the deceased in the realm of the dead. Thus, ushabtis played a vital role in ensuring the comfort and prosperity of the deceased in the afterlife, embodying the ancient Egyptian belief in eternal life and the continuity of existence beyond death.