Aramaic

Aramaic, a Semitic language with roots stretching back over three millennia, holds a central place in the linguistic history of the Near East.

Originating around the 10th c. BC in the region known as the Levant, Aramaic emerged as a spoken language among the Aramean tribes and gradually gained prominence due to its adaptability and practicality. With the expansion of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 8th c, BC, Aramaic became the lingua franca of the empire, spreading across vast territories as the language of administration, commerce, and diplomacy. This trend continued under subsequent empires, including the Neo-Babylonian and Persian Achaemenid Empires, solidifying Aramaic’s status as the primary language of communication throughout the Near East.

Its significance is underscored by its role in religious texts such as parts of the Hebrew Bible (particularly in the books of Daniel and Ezra) and portions of the New Testament, where it is believed to be the language spoken by Jesus Christ. Despite its decline as a spoken language, Aramaic continues to be used in liturgical settings among certain communities and is the subject of ongoing scholarly research. Through its rich history and enduring influence, Aramaic remains a testament to the cultural and linguistic diversity of the ancient Near East.

Alphabet

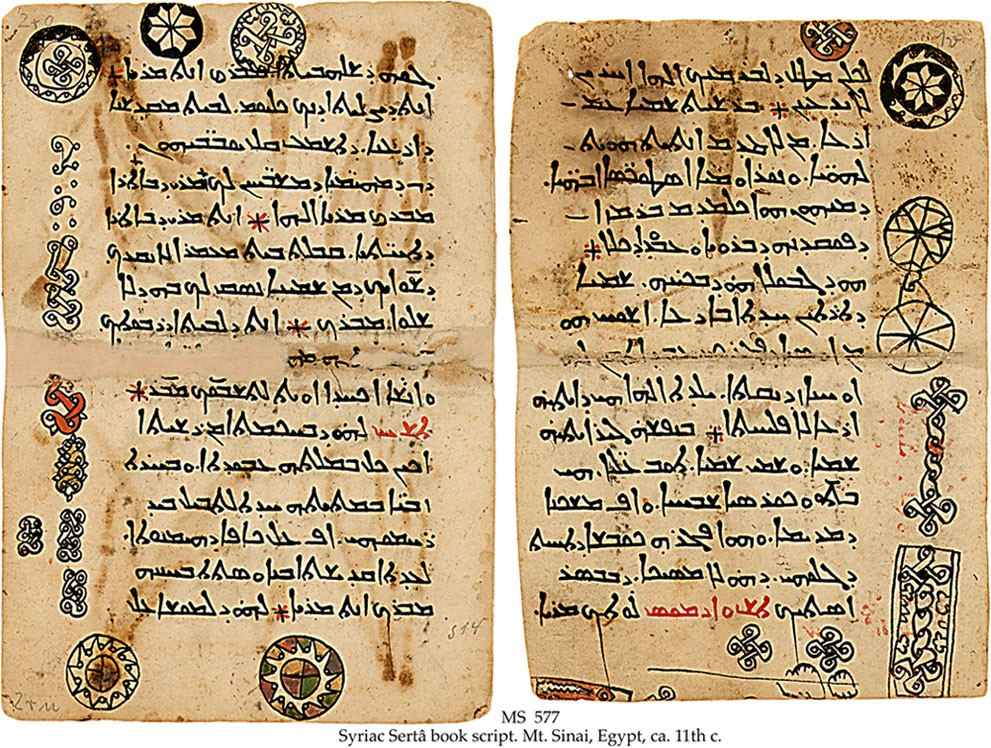

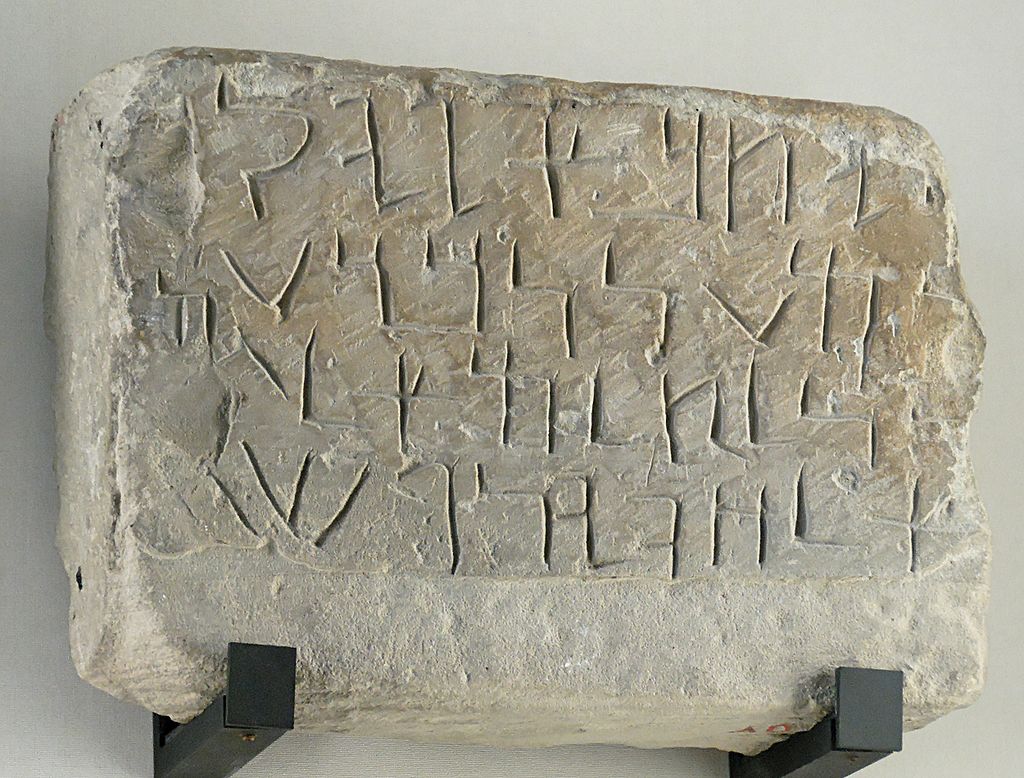

The Aramaic alphabet, a significant linguistic innovation adapted from the Phoenician script during the 8th c. BC, exerted a profound influence on the cultural and literary landscape of the ancient Near East.

Originally employed to transcribe the Aramaic language, this versatile writing system proved remarkably adaptable, evolving over time to accommodate the needs of various languages and cultures. Its enduring legacy is evidenced by its adaptation into a multitude of new alphabets, including the Hebrew square script and cursive script, Nabataean, Syriac, Palmyrenean, Mandaic, Sogdian, Mongolian, and likely the Old Turkic script. Spanning centuries of linguistic evolution, the Aramaic alphabet facilitated the expression of diverse languages and ideologies, leaving an indelible mark on the historical and cultural tapestry of the Near East and beyond.

Dialects

The Aramaic language, renowned for its adaptability and widespread usage, encompasses a diverse array of dialects that reflect the multifaceted linguistic landscape of the ancient Near East. Among the most notable Aramaic dialects are Eastern Aramaic, Western Aramaic, and Imperial Aramaic.

Eastern Aramaic dialects, spoken primarily in regions such as Mesopotamia and Persia, include Syriac, Mandaic, and Talmudic Aramaic, each exhibiting unique phonological, lexical, and grammatical features shaped by the cultural and historical contexts of their speakers.

Western Aramaic dialects, prevalent in territories like Syria and Palestine, comprise Palmyrenean, Samaritan, and Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, distinguished by their distinct regional influences and linguistic innovations.

Imperial Aramaic, the administrative and diplomatic language of ancient empires like Assyria and Babylon, served as a precursor to many later Aramaic dialects and played a pivotal role in the dissemination of Aramaic culture and literature throughout the Near East. Despite the diversity of Aramaic dialects, they share a common heritage and serve as a testament to the rich linguistic legacy of the ancient Near East.

Grammar

Aramaic grammar, characterized by its rich and intricate structure, reflects the linguistic sophistication of the ancient Near East. Like other Semitic languages, Aramaic exhibits a triliteral root system, where words are formed from a combination of consonantal roots and patterns, allowing for a wide range of derivations and meanings. Nouns in Aramaic are marked for gender, number, and case, with three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter) and three numbers (singular, dual, and plural). The language features a robust system of verbal conjugation, expressing tense, aspect, mood, and voice through a complex interplay of prefixes, suffixes, and vowel changes.

Aramaic also employs a variety of particles, conjunctions, and prepositions to convey nuanced relationships between words and clauses. Perhaps most notably, Aramaic utilizes a distinctive construct state to denote possession and attribution, whereby a genitive noun modifies its head noun, resulting in a possessive or descriptive relationship. Through its grammar, Aramaic provides a window into the linguistic and cultural heritage of the ancient Near East, illuminating the intricacies of communication and expression in this vibrant and enduring language.

Resources