Roman Sculpture

Examples of Roman sculpture are indeed abundantly preserved, presenting a stark contrast to Roman frescoes, which, despite their widespread production, have largely been lost to time. Descriptions of statues by Latin and Greek authors, notably Pliny the Elder in Book 34 of his Natural History, offer valuable insights into ancient artworks, with some descriptions matching extant pieces.

While a significant amount of Roman sculpture, especially in stone, has survived more or less intact, it often bears signs of damage or fragmentation. Life-size bronze statues, once prevalent, are now considerably rarer due to many having been recycled for their valuable metal content. Despite these challenges, Roman sculpture remains a rich source of artistic and historical significance, providing glimpses into the cultural and aesthetic preferences of ancient Rome.

Roman Portraiture will be dealt with in a separate section.

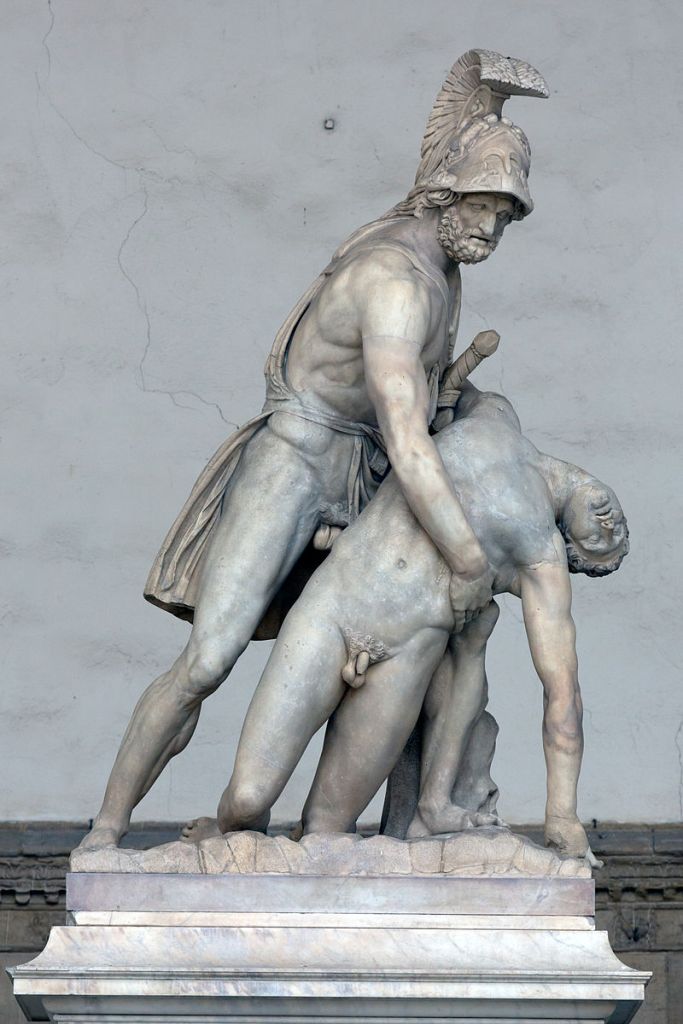

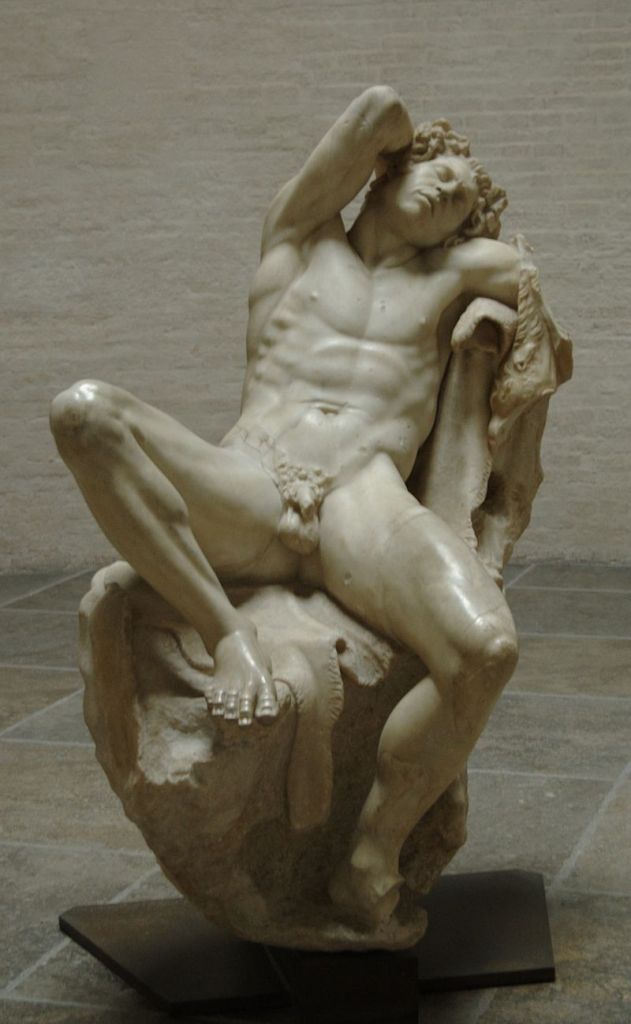

As the influence of the expanding Roman Republic spread into Greek territories, particularly in Southern Italy and later throughout the Hellenistic world, sculpture evolved as an extension of the prevalent Hellenistic style.

Distinguishing specifically Roman elements from this artistic amalgamation can be challenging, especially considering that much of the surviving Greek sculpture exists only in Roman copies. The Roman Republic’s conquests not only facilitated the spread of Greek artistic traditions but also fostered a synthesis of Greek and Roman cultural identities. Consequently, Roman sculpture of this period reflects a fusion of Hellenistic aesthetics with emerging Roman sensibilities, marking a pivotal juncture in the development of Roman art.

2. Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, Roman copy of Hellenistic original, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence. (c) Morio

3. Barberini Faun, Roman copy of Hellensitic original. Glyptotek, Munich.

4. Diana of Versailles. Roman copy of a lost Greek bronze original attributed to Leochares, c. 325 BC. (c) Commonist

5. Ludovisi Ares. Roman 2nd c. AD copy of a late 4th c. BC Greek original, associated with Scopas or Lysippus. Palazzo Altemps, Rome.

6. Dying Gaul. Roman copy of Hellenistic bronze original. (c) ChrisO

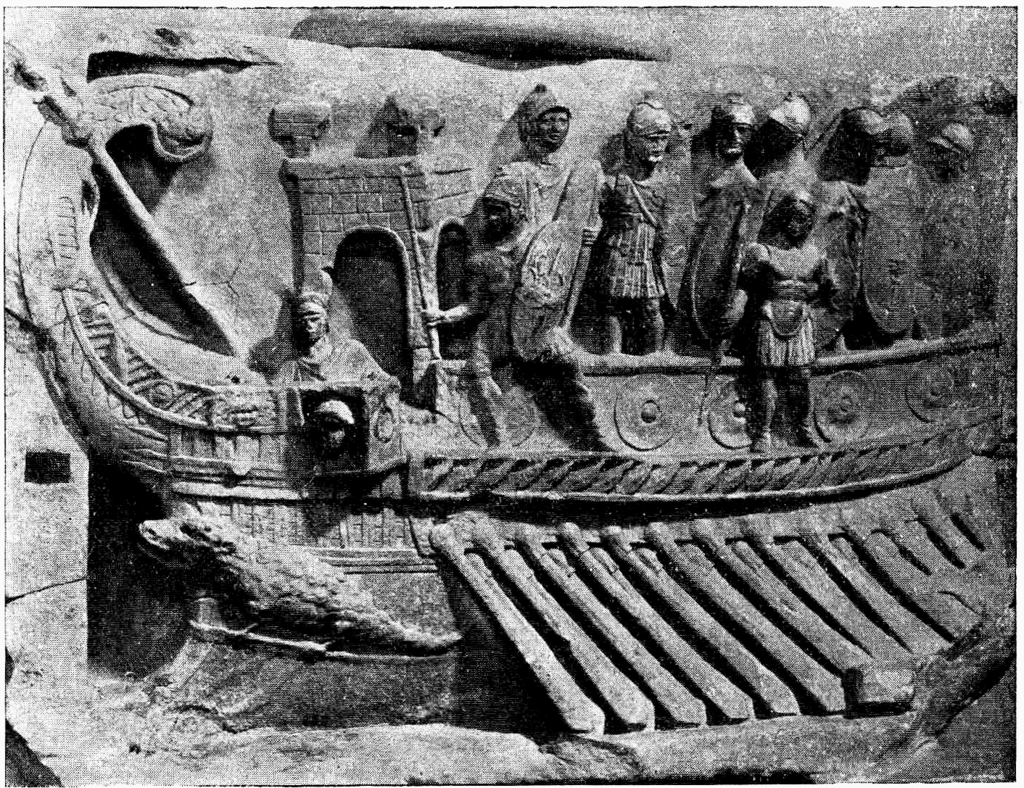

Reliefs

The Romans diverged from the Greek tradition of creating free-standing sculptures depicting heroic exploits from history or mythology. Instead, they focused on producing historical works predominantly in relief form from an early period.

This shift in artistic expression allowed the Romans to showcase their narratives and commemorate significant events through intricate reliefs carved into various mediums such as stone, marble, and metal. Unlike the standalone grandeur of Greek sculptures, Roman reliefs often adorned public monuments, triumphal arches, and sarcophagi, serving as visual narratives that celebrated military victories, imperial achievements, and historical events. This emphasis on relief sculpture underscored the Romans’ penchant for storytelling and their desire to immortalize their legacy through intricate and enduring artistic expressions.

Triumphal Columns

Roman relief sculpture reached new heights of complexity and grandeur during the 2nd c. AD, particularly with the construction of the famous Trajan’s Column and Marcus Aurelius’ Column.

These monumental structures, erected in Rome to commemorate the military campaigns of the respective emperors, showcased continuous narrative reliefs spiraling around their exteriors. The reliefs depicted detailed scenes of battles, sieges, and triumphs, meticulously carved to convey the military prowess and victories of the Roman legions. Trajan’s Column, completed in 113 AD, stands as a towering testament to the emperor’s conquest of Dacia (modern-day Romania), while Marcus Aurelius’ Column, completed in 193 AD, immortalizes his campaigns against the Germanic tribes along the Danube frontier.

These columns not only served as monumental landmarks in the city but also as visual chronicles of imperial power and military glory, demonstrating the Romans’ mastery of relief sculpture as a powerful tool for propagating political and military achievements.

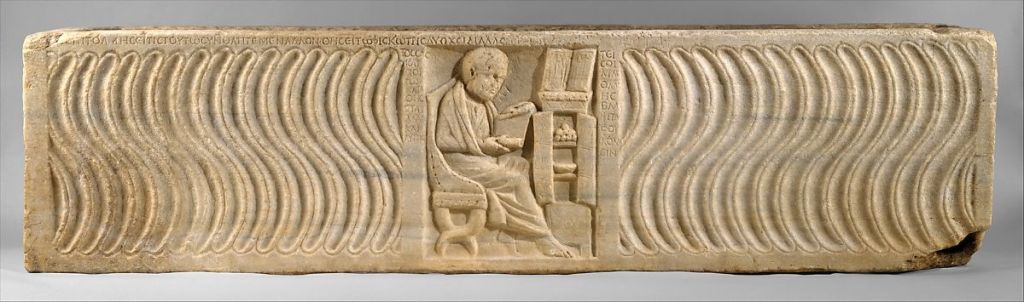

Sarcophagi

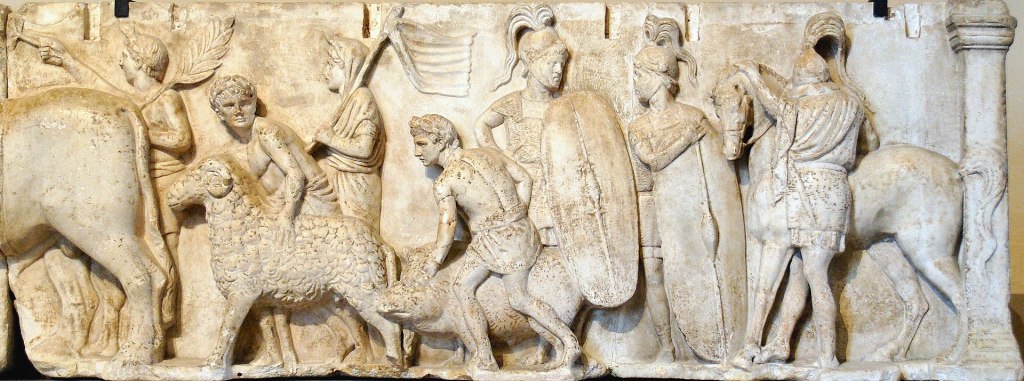

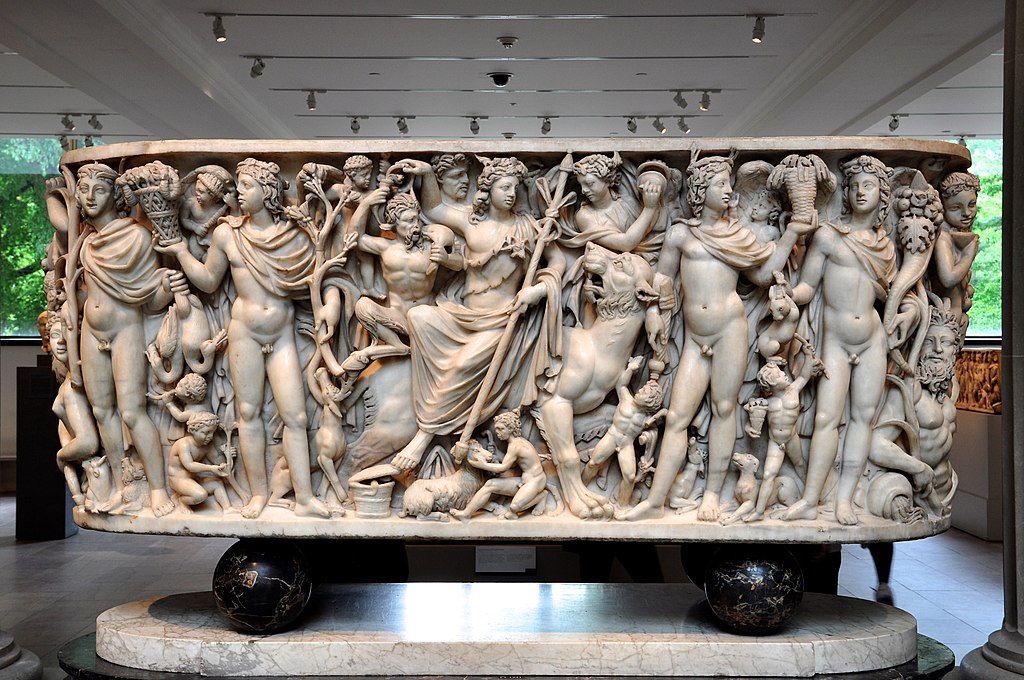

Elaborately carved marble and limestone sarcophagi adorned with intricate relief sculptures became characteristic features of elite Roman burials during the 2nd-4th c. AD.

These sarcophagi served as ornate containers for the remains of the deceased, showcasing scenes from mythology, daily life, and religious beliefs intricately carved into their surfaces. The reliefs depicted various themes such as funerary rituals, scenes of the afterlife, and mythological narratives, often imbued with symbolism and significance to the deceased and their family.

At least 10,000 Roman sarcophagi have endured the passage of time, with fragments potentially representing as many as 20,000. While mythological scenes are prevalent, sarcophagi reliefs also portray a diverse range of subjects, including depictions of the deceased’s occupation, military exploits, and various aspects of daily life. These reliefs offer a vivid glimpse into the multifaceted identities and experiences of the individuals interred within, showcasing their roles in society, achievements, and personal interests.

From scenes of agricultural labor to elaborate military processions, the reliefs on Roman sarcophagi provide valuable insights into the social, cultural, and historical context of ancient Roman life.