Sumerian Art

Sumerian art is renowned for its intricate detail and lavish ornamentation, often incorporating a diverse array of materials sourced from distant lands. Semi-precious stones like lapis lazuli, marble, and diorite, along with precious metals such as hammered gold, were skillfully integrated into the design of their artifacts, adding to their opulence and prestige.

While stone was a rare commodity reserved primarily for sculpture, clay emerged as the predominant medium due to its abundance in Sumer. Consequently, many Sumerian artifacts, including their iconic cuneiform tablets, were crafted from clay. Metals like gold, silver, copper, and bronze, as well as shells and gemstones, were reserved for the finest sculptures and intricate inlays, showcasing the sophistication of Sumerian craftsmanship. Cylinder seals, vital for administrative and commercial purposes, often featured small precious stones like lapis lazuli, alabaster, and serpentine.

The Royal Cemetery of Ur, meticulously excavated by Leonard Woolley between 1922 and 1934, stands as a treasure trove of Sumerian art, offering invaluable insights into the artistic prowess and cultural richness of ancient Sumer.

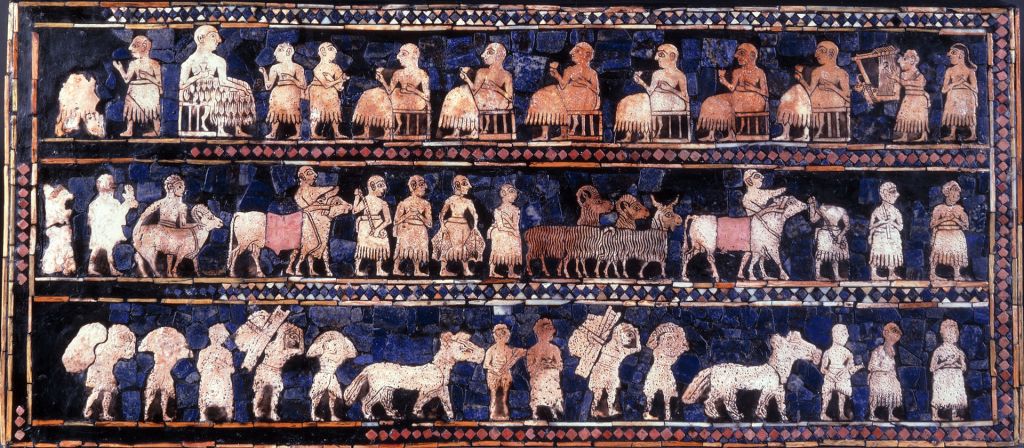

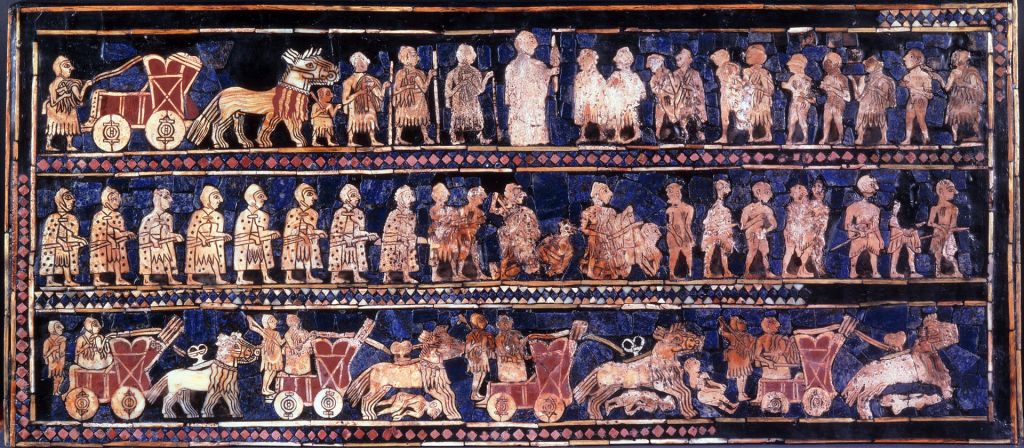

The Standard of Ur

Dating back to c. 2600 BC, the enigmatic artifact known as the Standard of Ur captivates with its enigmatic construction and intricate symbolism. Crafted in the form of a hollow wooden box, its sides are adorned with elaborately inlaid mosaics depicting scenes of both war and peace.

Discovered in a royal tomb within the ancient city of Ur during the 1920s, its original purpose continues to elude scholars, sparking ongoing debate and speculation. While initially interpreted as a standard, its true function remains shrouded in mystery. Adding to its mystique, the standard was found alongside the remains of a ritually sacrificed individual, suggesting a possible connection between the artifact and its bearer. Despite the passage of millennia, the standard from Ur continues to intrigue and perplex, serving as a tangible link to the rich tapestry of ancient Mesopotamian civilization.

Ram in a Thicket

The Ram in a Thicket, a remarkable pair of figures unearthed in Ur and dating back to c. 2600–2400 BC, stands as a testament to the exquisite craftsmanship of ancient Mesopotamian artisans. Adorned with luxurious materials meticulously applied, these figures exhibit a striking combination of gold leaf, copper, lapis lazuli, and shell.

The ram’s head and legs, coated in shimmering gold leaf, are affixed to the wooden structure with a delicate wash of bitumen, while its ears boast intricate copper detailing. The horns and fleece, crafted from precious lapis lazuli, lend a regal aura to the figure, while the body’s fleece, composed of shell, adds texture and depth. The figure is elevated further by a silver-plated belly and a tree adorned with golden leaves and flowers. Resting upon a base adorned with a mosaic of shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli, the Ram in a Thicket stands as a masterpiece of ancient artistry, offering a glimpse into the sophisticated aesthetic sensibilities of the Sumerian civilization.

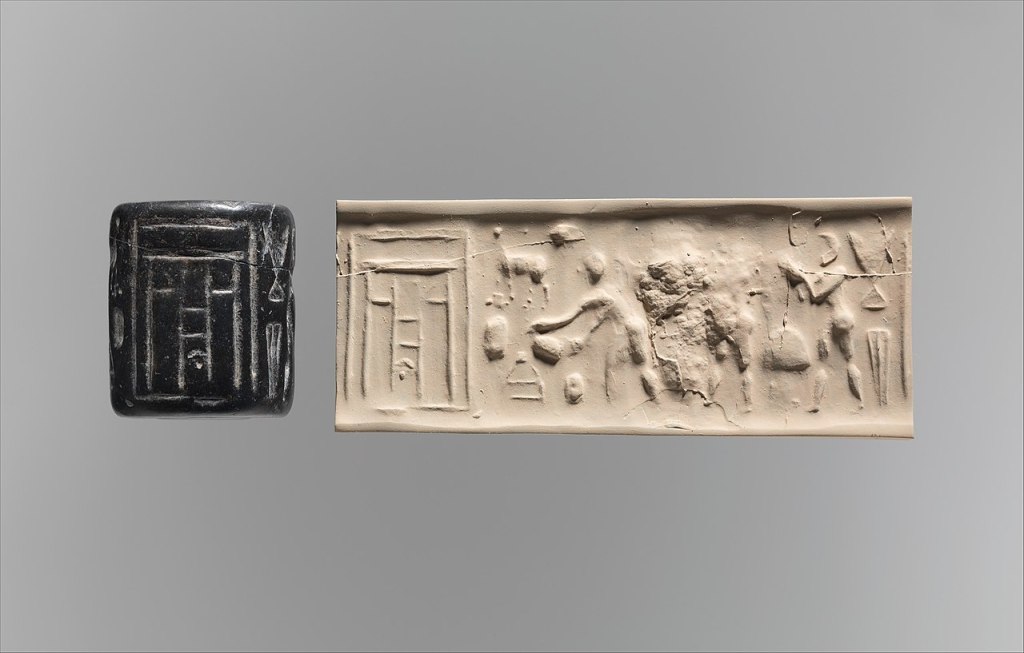

Cylinder Seals

In ancient Sumer, the cylinder seal emerged as a quintessential artifact, serving as both a practical tool and a vehicle for artistic expression. These small, cylindrical objects, typically measuring about one inch in length, were intricately engraved with written characters, figurative scenes, or a combination of both.

Employed to roll impressions onto wet clay surfaces, cylinder seals played a crucial role in Sumerian administrative and economic activities, serving as signatures, official marks, and identifiers of ownership. Beyond their utilitarian function, these seals also showcased the artistic prowess of Sumerian craftsmen, featuring elaborate depictions of mythology, religious beliefs, daily life, and royal rituals.

Other Grave Goods from Ur

The Warka Vase

The Warka Vase stands as a remarkable testament to the artistic and religious sophistication of ancient Sumer. Crafted from carved alabaster and discovered within the temple complex dedicated to the Sumerian goddess Inanna in the ruins of Uruk, this slender vessel dates back to c. 3200–3000 BC. Remarkably, it ranks among the earliest surviving examples of narrative relief sculpture, akin to the significance of the Narmer Palette from Egypt and the Uruk Trough.

The intricate narrative depicted on the Warka Vase offers a vivid portrayal of Sumerian life and religious beliefs. The bottom register showcases scenes of agricultural abundance, featuring representations of water, date palms, barley, and wheat, symbolizing fertility and prosperity. Above, a procession of rams and ewes marches in a single file, perhaps evoking rituals associated with fertility and animal husbandry.

In the middle register, the depiction of naked men carrying baskets of foodstuffs signifies offerings made to the divine. These offerings, presented in reverence, underscore the importance of religious devotion in Sumerian society. At the apex of the vase, the goddess Inanna herself takes center stage, surrounded by the opulence of her shrine and storehouse. This scene likely represents the ritual marriage between Inanna and Dumuzi, her consort, a sacred union believed to ensure the continued vitality and prosperity of Uruk.

Sculpture

Sumerian sculpture is characterized by its intricate detail, symbolic imagery, and religious significance. Sculptors in Sumer employed a variety of materials, including clay, alabaster, limestone, and precious metals, to craft their works of art.

Iconic examples of Sumerian sculpture include the statues of deities and rulers, such as the votive statues of worshipers with clasped hands and the famous statues of Gudea, the ruler of the city-state of Lagash. These sculptures often served religious and ceremonial purposes, depicting gods, goddesses, and royal figures in elaborate ceremonial attire and symbolic poses.