The Severan Dynasty (193-235 AD)

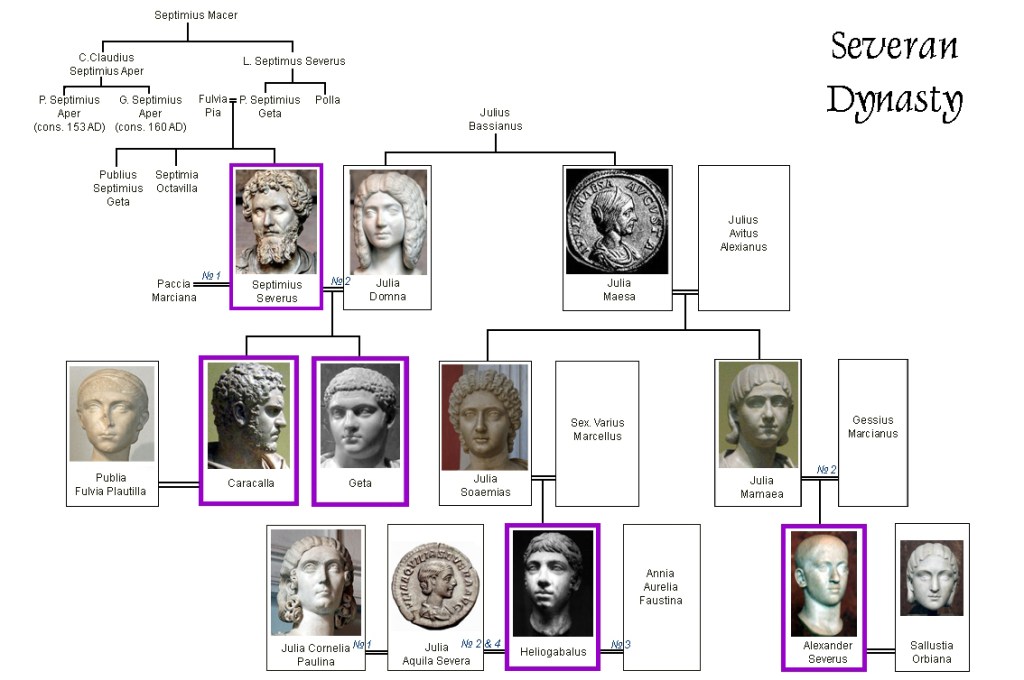

The Severan dynasty emerged as the fourth imperial dynasty of Rome, spanning from 193-235 AD. Led by a succession of emperors including Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Geta, Elagabalus, and Alexander Severus, this period was marked by significant political upheaval, military campaigns, and cultural changes within the Roman Empire

The Severan dynasty faced interruptions and challenges during its reign, notably during the joint rule of Macrinus and his son Diadumenian in 217-218 AD following the assassination of Caracalla. This period marked a significant deviation from the direct line of succession within the Severan family.

The Severan women played crucial roles in the political landscape of the dynasty, exerting significant influence and power. Julia Domna, the mother of Caracalla and Geta, was a prominent figure at the imperial court and played a pivotal role in shaping her sons’ policies and decisions. Her nieces, Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea, who were the mothers of Elagabalus and Alexander Severus respectively, similarly wielded considerable influence over their sons’ reigns.

Julia Maesa, the mother of Julia Domna and Julia Soaemias, emerged as a particularly influential figure within the dynasty. Through her political acumen and strategic alliances, she played a key role in securing the imperial positions of her grandsons, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus. Julia Maesa’s efforts helped to maintain the continuity of the Severan dynasty despite the challenges it faced during this period.

Under Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus’s rise to power in 193 AD marked a pivotal moment in Roman history, occurring during the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors. Following the assassination of Emperor Pertinax by the Praetorian Guard, Severus, then governor of Pannonia Superior, seized the opportunity to claim the imperial throne.

Severus was acclaimed emperor by his troops and swiftly marched on Rome, capitalizing on the chaos and instability within the empire. Upon his arrival, he deposed Didius Julianus, who had obtained the throne through the machinations of the Praetorian Guard and a corrupt auction.

With his hold on power secured in Rome, Severus faced opposition from rival claimants to the imperial throne. He first confronted Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria. In 194 AD, Severus decisively defeated Niger’s forces at the Battle of Issus. Subsequently, Severus turned his attention to Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britannia. In 197 AD, Severus clashed with Albinus’s forces at the Battle of Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon), emerging victorious and consolidating his control over the empire.

Septimius Severus’s reign was characterized by a series of military campaigns and ambitious building projects, as well as significant economic policies that would have lasting effects on the Roman Empire.

In addition to securing his hold on power through his civil wars and defeating rival claimants to the throne, Severus embarked on military campaigns against external foes. In 197 AD, he launched a campaign against the Parthians, seeking to assert Roman dominance in the East. Additionally, in 209-210 AD, Severus led a campaign against the Caledonians in northern Britannia, where he sought to strengthen Roman control over the region and defend the empire’s northern frontier. As part of this effort, Severus reinforced Hadrian’s Wall and re-occupied the Antonine Wall, fortifying Roman defenses in Britain.

Severus was also renowned for his building projects, both in Rome and in his native city of Leptis Magna. The Arch of Septimius Severus and the Septizodium in Rome stand as enduring monuments to his reign, showcasing his commitment to architectural splendor and imperial grandeur.

However, Severus’s economic policies, particularly his decision to debase the Roman currency, had significant consequences. By reducing the value of Roman coinage, Severus sought to finance his military campaigns and maintain imperial control. However, this policy ultimately led to inflation and economic instability, contributing to the long-term decline of the Roman economy.

Severus’s death in early 211 AD, while on campaign in Caledonia, marked the end of his reign. He was succeeded by his two sons, Caracalla and Geta, who would go on to rule as joint emperors, albeit with a tumultuous relationship that would ultimately lead to tragedy.

Under Caracalla

Caracalla’s reign was marked by a combination of military campaigns, significant legislative reforms, and the consolidation of imperial power, as well as internal intrigue and violence.

Upon the death of his father, Caracalla ruled jointly with his brother Geta. However, their relationship quickly deteriorated, leading Caracalla to have Geta murdered by the Praetorian Guard in late 211 AD, allowing him to rule as sole emperor. This act of fratricide underscored Caracalla’s ruthless and authoritarian tendencies.

Preferring military exploits to administrative duties, Caracalla delegated much of the governance of the empire to his mother and court officials. He embarked on military campaigns against the Alamanni in 213-214 AD and the Parthians in 216 AD.

One of Caracalla’s most notable achievements was the Edict of Caracalla in 212 AD, which granted Roman citizenship to all free men within the empire. This sweeping reform aimed to increase loyalty to the imperial government and integrate diverse populations within the empire.

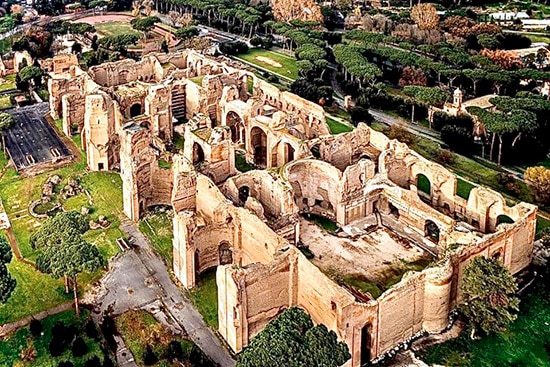

Caracalla’s reign also saw significant architectural projects, including the construction of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, one of the largest and most luxurious public bath complexes in the ancient world. Additionally, Caracalla introduced a new currency, the Antoninianus, a double denarius, in an effort to address economic issues and stabilize the empire’s finances.

Despite his military successes and legislative reforms, Caracalla’s reign was marred by violence and instability. His assassination on March 8th, 217 AD, by a disaffected soldier while en route to Carrhae, marked the end of his tumultuous reign. Caracalla was succeeded by his Praetorian Prefect, M. Opellius Macrinus.

Under Geta

The joint rule of Geta and Caracalla, following the death of their father Septimius Severus, was marked by intense rivalry and a complete inability to share power. Despite their shared authority, the brothers proved incapable of cooperation, leading to a tense and divided atmosphere within the imperial palace in Rome.

To mitigate the risk of assassination from each other, the palace was divided into separate sections, and Geta and Caracalla only met in the presence of their mother, Julia Domna, accompanied by bodyguards. However, even these precautions were insufficient to prevent escalating tensions between the brothers.

The stability of their joint reign was largely upheld through the mediation and leadership of their mother, Julia Domna, as well as other senior courtiers and generals who sought to maintain order and prevent open conflict between the siblings. However, by the end of 211 AD, the situation had become untenable, and Caracalla decided to take drastic action to eliminate his brother and consolidate his power.

Caracalla orchestrated a peace meeting between himself and Geta in their mother’s apartments, during which Geta was deprived of his bodyguards. In a treacherous act, Caracalla then had Geta murdered in their mother’s arms by his Praetorian Guard. Subsequently, Caracalla declared a Damnatio Memoriae on Geta, seeking to erase his brother’s memory from history and secure his own dominance as sole emperor.

Under Elagabalus

Elagabalus’s ascension to the imperial throne at the age of fourteen marked a tumultuous period in Roman history, characterized by political intrigue, religious controversy, and scandalous behavior. His rise to power was orchestrated by his grandmother, Julia Maesa, who engineered a revolt against Macrinus in the East, paving the way for Elagabalus’s acclaimed as emperor in 218 AD.

Prior to his elevation as emperor, Elagabalus had served as the high priest of the god Elagabal, from whom he derived his name. His reign was defined by a series of scandalous episodes and religious innovations that scandalized traditional Roman sensibilities.

Elagabalus disregarded the worship of traditional Roman gods and sought to impose the cult of Elagabal as the primary religion of the empire, replacing Jupiter with his patron deity. His attempts to impose his religious beliefs alienated many, including the Praetorian Guard, the Senate, and the common people, who viewed his actions as blasphemous and sacrilegious.

Moreover, Elagabalus’s personal conduct further exacerbated tensions within the empire. He engaged in scandalous behavior, including marrying four women, one of whom was a Vestal Virgin, a grave offense in Roman society. Additionally, he lavished favors on male courtiers believed to be his lovers, further fueling controversy and disdain among the populace.

In the face of mounting opposition and discontent, Elagabalus’s reign proved short-lived. In March 222 AD, he was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard on the orders of his grandmother, Julia Maesa, who sought to install his cousin Alexander Severus as emperor in his place.

Under Alexander Severus

Alexander Severus’s ascension to the imperial throne at a young age presented significant challenges, necessitating reliance on the guidance and counsel of his grandmother Julia Maesa and mother Julia Mamaea during his early reign. Despite his lack of experience, Alexander’s rule was initially characterized by prosperity and relative stability.

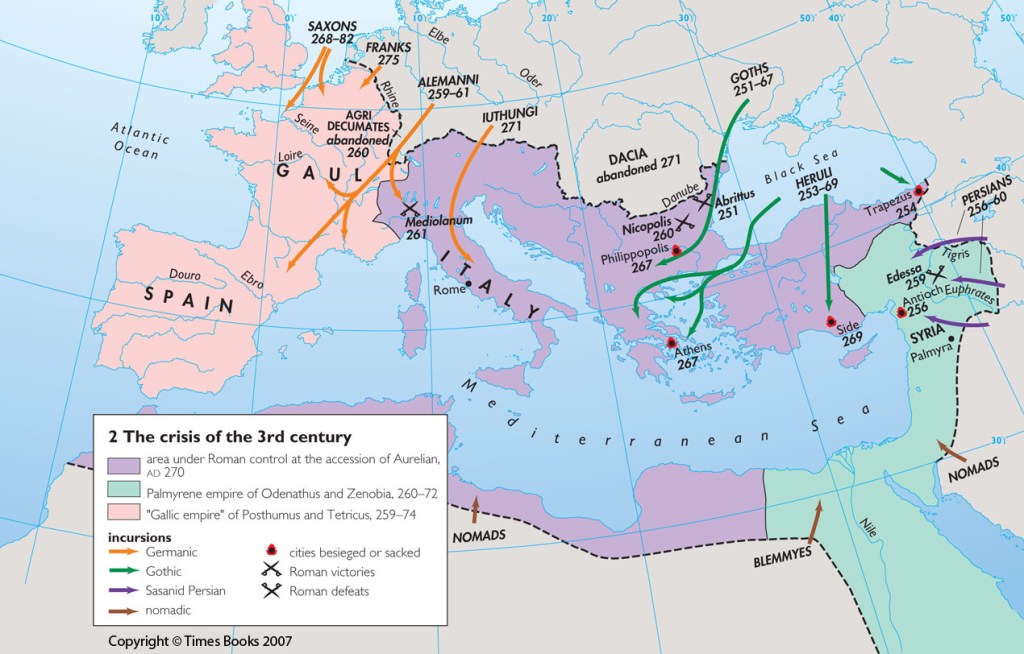

However, in 231 AD, Alexander faced a formidable threat in the form of the rising power of the Sassanid Empire. To counter this threat, he launched a series of campaigns aimed at checking the advances of the Sassanids, demonstrating his determination to defend the eastern borders of the Roman Empire.

Despite his successes against the Sassanids, Alexander encountered further challenges in 234 AD with the invasion of Germanic tribes. Rather than resorting to military confrontation, Alexander attempted to resolve the conflict through diplomacy and bribery, seeking to secure peace and stability for the empire. However, this approach proved divisive and alienated the Roman army, which grew increasingly discontented with his leadership.

The discontent within the Roman army ultimately culminated in a mutiny, leading to the assassination of Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea on March 22nd, 235 AD, at Mainz. This violent act marked the end of Alexander’s reign and precipitated the onset of the Crisis of the Third Century, a period of political instability, economic turmoil, and military upheaval that would profoundly impact the Roman Empire for decades to come.

Alexander Severus’s death symbolized the collapse of centralized authority and the onset of a period of internal strife and external threats that would test the resilience of the Roman Empire and contribute to its eventual decline.