The Flavian Dynasty (69-96 AD)

The Flavian dynasty emerged as the second Roman imperial dynasty, comprising Vespasian and his two sons, Titus and Domitian. Their reign spanned from 69-96 AD, a period marked by significant political, military, and cultural developments in the Roman Empire.

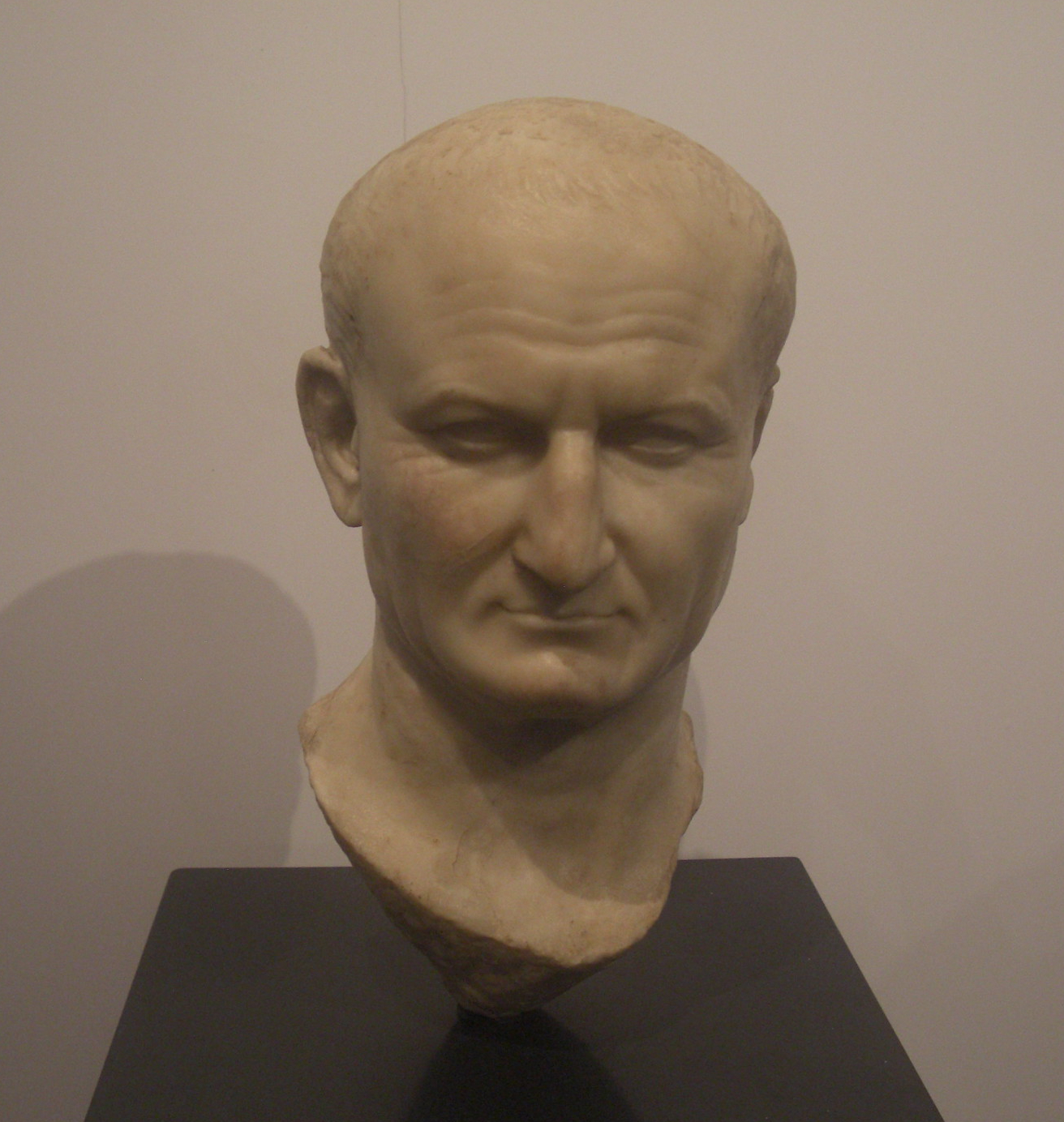

The Flavian dynasty ascended to power amidst the chaos of the civil war in 69 AD, famously known as the Year of the Four Emperors. Vespasian, a skilled military commander with a distinguished career, emerged as the victor of this tumultuous period, securing the imperial throne and laying the foundation for his family’s dynasty.

Following the brief reigns of Galba and Otho, Vitellius emerged as emperor, only to face a formidable challenge from Vespasian, commander of the Eastern Legions.

The Eastern Legions, under Vespasian’s leadership, declared him emperor in opposition to Vitellius. This declaration led to a decisive confrontation between the forces of Vespasian and Vitellius at the Second Battle of Bedriacum. Vespasian emerged victorious, culminating in his triumphant entry into Rome on December 20th.

The Roman Senate, recognizing Vespasian’s military success and political support, officially declared him emperor on the following day, solidifying his position as the new ruler of the Roman Empire.

Under Vespasian

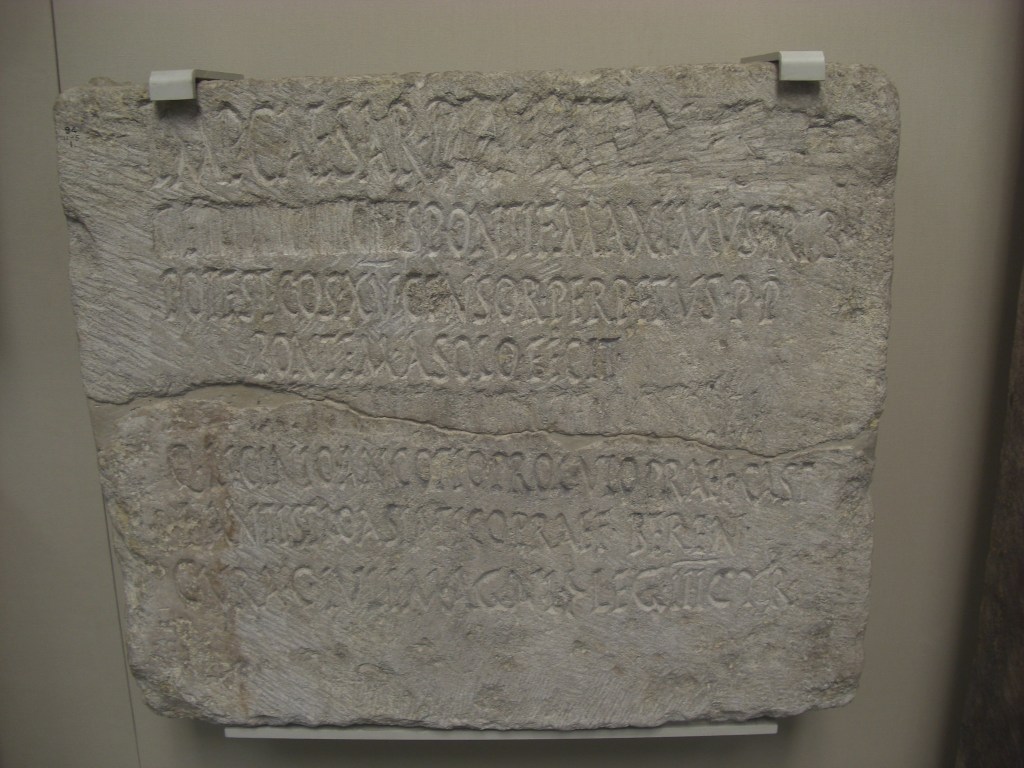

Vespasian’s tenure as emperor indeed began with a focus on consolidating his power and stabilizing the Roman Empire. Spending his first year as emperor in Egypt, he aimed to shore up support in the East while delegating the administration of the empire to capable individuals, notably C. Licinius Mucianus, who was aided by Vespasian’s son, Domitian.

Upon his arrival in Rome in the summer of 70 AD, Vespasian embarked on an extensive propaganda campaign to solidify his authority and promote the new Flavian dynasty. His efforts included financial reforms, such as the introduction of the tax on public toilets, which aimed to bolster the empire’s revenue and address fiscal challenges.

Vespasian’s reign was marked by various military campaigns, including the Batavian Revolt and the First Jewish-Roman War. The latter culminated in the siege and destruction of Jerusalem by his son Titus in 70 AD, a significant event that reshaped the political and religious landscape of the region.

Furthermore, Vespasian initiated ambitious building projects in Rome, adding to the city’s architectural splendor. Among these projects were the construction of the Forum of Vespasian and the Temple of Peace, as well as the commencement of the Flavian Amphitheatre, which would later become known as the Colosseum, one of the most iconic structures of ancient Rome.

Vespasian’s reign was characterized by pragmatic governance, military success, and significant contributions to Roman infrastructure and culture. He died from natural causes on June 23, 79 AD and was succeeded by his eldest son Titus.

Under Titus

Titus’s brief reign as emperor was indeed marked by significant accomplishments and widespread acclaim among ancient authors. Following in his father Vespasian’s footsteps, Titus continued the public building program in Rome, most notably overseeing the completion of the Flavian Amphitheatre in 80 AD.

Titus’s reputation as a capable ruler was further solidified by his adept handling of two major disasters during his reign: the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and the fire of Rome in 80 AD. His swift and effective response to these crises earned him praise for his leadership and compassion towards his subjects.

Additionally, Titus revived the practice of the Imperial Cult, honoring his father Vespasian by deifying him and initiating the construction of the Temple of Vespasian and Titus. Although the temple was completed by Titus’s brother Domitian, its establishment symbolized Titus’s reverence for his father and his commitment to perpetuating the Flavian legacy.

Despite his relatively short reign of just over two years, Titus’s unexpected death from a fever on September 13, 81 AD, marked the end of a promising reign. His passing paved the way for his younger brother Domitian to ascend to the imperial throne.

Under Domitian

Domitian’s lengthy reign indeed marked a period of significant achievements and challenges for the Roman Empire. With a tenure exceeding fifteen years, it was the longest since Tiberius, showcasing his ability to maintain stability and authority over an extended period.

Economically, Domitian implemented reforms aimed at strengthening the Roman monetary system, including the revaluation of currency. These measures helped stabilize the economy and bolstered confidence in the Empire’s financial stability.

Domitian also prioritized the defense of the empire’s borders, recognizing the importance of maintaining strong military defenses to safeguard against external threats. He continued his family’s tradition of undertaking building projects to restore Rome after the devastating fire of 80 AD, contributing to the city’s reconstruction and revitalization.

Militarily, Domitian achieved notable success in Britain, where his governor Cn. Julius Agricola expanded Roman control into Scotland, consolidating Roman influence in the region. However, Domitian faced challenges in the east, particularly with the Dacian tribes, ultimately resorting to a peace treaty rather than achieving a decisive military victory.

Despite his popularity among the common people, Domitian’s reign was marked by strained relations with the Roman Senate. His autocratic tendencies and efforts to centralize power led to conflicts with the Senate, further exacerbating tensions between the emperor and the political elite.

On September 18, 96 AD, Domitian was assassinated by court officials, bringing an abrupt end to the Flavian dynasty.

After his death the Roman Senate passed a Damnatio Memoriae on Domitian, which meant that his name was erased from public monuments and his statues were torn down. Ancient authros tend to portray Domitian as a cruel and paranoid tyrant. However, modern historians has rejected these views, instead characterising him as a ruthless but efficient autocrat, whose cultural, economic and political programme provided the foundation for the Principate of the peaceful 2nd c. AD.

His longtime advisor Nerva succeeded him, marking the beginning of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. Nerva’s reign represented a shift towards a more moderate and inclusive form of governance, laying the groundwork for the subsequent era of peace and prosperity under the Antonine emperors.