The Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 BC – 68 AD)

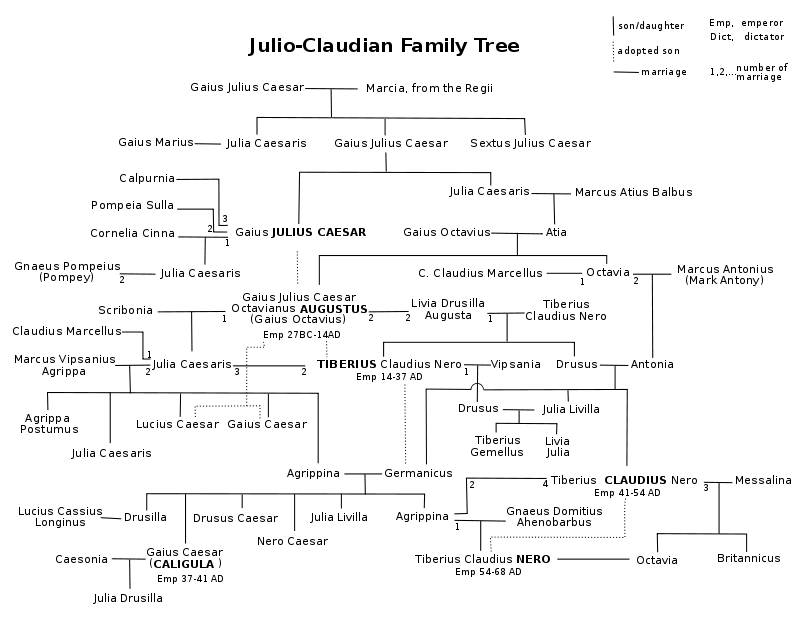

The Julio-Claudian dynasty, regarded as the inaugural Roman imperial dynasty, encompassed the reigns of the first five emperors: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. This dynasty governed the Roman Empire from its establishment under Augustus in 27 BC until the demise of Nero in 68 AD, who commited suicide. The term “Julio-Claudian” originates from the two principal branches of the imperial family: the Julii Caesares and the Claudii Nerones.

The Julio-Claudian emperors faced challenges in securing a suitable male heir, leading them to adopt successors to maintain dynastic continuity. Augustus, who himself was adopted by Julius Caesar, chose his stepson Tiberius as his heir. Tiberius, in turn, adopted his nephew Germanicus, Caligula’s father and Claudius’s brother. Caligula later adopted his cousin Tiberius Gemellus shortly before executing him. Finally, Claudius adopted his great-nephew Nero, as his son was too young. However, Nero’s reign marked the decline of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, culminating in his fall from power and eventual suicide, thus bringing an end to the dynasty’s rule, as Nero had no heir.

Under Augustus

Augustus’s legacy as the founder of the Roman Empire and its first emperor places him among history’s most esteemed leaders. His reign marked the onset of the Pax Romana, a remarkable two-century era characterized by Roman expansion, peace, and prosperity. Augustus skillfully restored the semblance of the Roman Republic, distributing governmental powers among the Senate, executive magistrates, and legislative assemblies, while retaining considerable autocratic authority conferred by the Senate.

He orchestrated a vast expansion of the Empire, annexing territories like Dalmatia, Egypt, Noricum, Pannonia, and Raetia into provinces, and completing the conquest of Hispania. Despite initial successes in Germania, Augustus faced setbacks, notably the Varian Disaster of 9 AD, which compelled him to acknowledge the Rhine as the northern frontier. Augustus implemented significant reforms, overhauling the taxation system, enhancing the Empire’s infrastructure with an official courier network, instituting a standing army, and establishing elite units such as the Praetorian Guard. His ambitious building projects transformed Rome, earning him the epithet of leaving behind “a Rome of marble.”

Augustus’s passing in 14 AD at age 75 marked the end of an illustrious era, succeeded by his stepson Tiberius, though speculation persists regarding the circumstances of his death, including rumors of poisoning by his wife Livia.

Under Tiberius

Tiberius’s ascent to the role of emperor indeed seemed marked by a reluctance stemming from his strained relationship with the Senate and a general distrust of political circles. His early years in power were overshadowed by his struggle to navigate the complexities of Roman politics, exacerbated by personal losses such as the deaths of his nephew Germanicus in 19 AD and his son Drusus in 23 AD.

Despite these challenges, Tiberius exhibited a keen aptitude for administration, implementing policies that strengthened the Empire economically and militarily. His tenure saw the consolidation of Roman territories and the stabilization of borders, contributing to the overall prosperity and security of the Empire.

However, following the aforementioned personal tragedies, Tiberius increasingly withdrew from public life, becoming reclusive and aloof. His retreat to the villa on Capri in 26 AD marked a turning point in his reign, as he delegated much of the day-to-day governance to trusted advisors, notably the Praetorian Prefect Sejanus.

Sejanus’s influence grew substantially during this period, but it ultimately led to his downfall. Tiberius, recognizing the threat posed by Sejanus’s ambition and machinations, ordered his execution for treason. This event underscores Tiberius’s willingness to assert control over his administration and protect the stability of the Empire, even at the expense of those once considered close allies.

The reverse reads Augusta Bilbilis Ti(berius) Caesare L(ucius) Aelio Seiano, marking the consulship of Sejanus in that year. (c) ForumRomanCoins

Tiberius’s death at Misenum on March 16, 37 AD, marked the end of his controversial reign. According to accounts by Suetonius, it’s suggested that Tiberius’s Praetorian Prefect, N. Sutorius Macro, may have played a role in hastening his demise to facilitate the accession of Caligula to the imperial throne.

Under Caligula

Caligula’s reign indeed began with promise, characterized by competent governance during its initial phase. However, a significant shift occurred following his recovery from illness, marking the onset of a darker and more tyrannical period that tarnished his reputation in history.

During the first six months of his rule, Caligula demonstrated administrative prowess and made notable accomplishments, such as the annexation of the kingdom of Mauretania and the initiation of ambitious infrastructure projects in Rome, including the construction of two new aqueducts, the Aqua Claudia and the Aqua Anio Novus.

However, Caligula’s behavior later became erratic and tyrannical, as evidenced by reports of cruelty, sadism, extravagance, and sexual perversion. These accounts, although partly sensationalized, paint a picture of an increasingly despotic ruler whose actions alienated many within the political and social elite of Rome. One of the most infamous episodes of Caligula’s reign was his failed attempt to invade Britannia, which highlighted both his ambition and recklessness as a leader. This military venture ended in humiliation and further fueled discontent among his subjects.

The turning point came on January 24, 41 AD, when Caligula was assassinated as a result of a conspiracy involving officers of the Praetorian Guard, senators, and courtiers. This event, orchestrated by those disillusioned with Caligula’s rule, led to a power vacuum in Rome. In a twist of fate, the Praetorian Guard declared Caligula’s uncle, Claudius, as emperor after finding him hiding behind a curtain in the palace.

Under Claudius

Claudius, despite being underestimated due to physical disabilities and a lack of political experience, emerged as a surprisingly adept ruler following the tumultuous reign of Caligula. His tenure as emperor witnessed significant administrative reforms and infrastructure developments that left a lasting impact on the Roman Empire.

One of Claudius’s notable achievements was the expansion of the imperial bureaucracy to include freedmen, a move aimed at broadening the base of administrative talent and reducing the influence of traditional elite factions. This inclusive approach helped stabilize the government and ensured a more efficient functioning of state affairs. Furthermore, Claudius worked diligently to replenish the treasury, which had been depleted by the excesses of Caligula’s reign. His financial policies focused on fiscal responsibility and prudent management, which helped restore economic stability to the Empire.

Claudius also embarked on ambitious public works projects aimed at improving infrastructure across the Empire. The construction of Portus, a new harbor for Rome, stands out as a significant achievement, facilitating maritime trade and bolstering the city’s economic prominence. Additionally, Claudius oversaw the building of numerous roads and canals, enhancing communication and transportation networks throughout the Empire.

Military conquests further solidified Claudius’s reign. The successful invasion of Britannia in 43 AD marked a significant expansion of Roman territory and strengthened Claudius’s relationship with the Roman Army. This military victory not only secured valuable resources but also bolstered Claudius’s prestige and legitimacy as a capable leader.

However, Claudius’s life was cut short by betrayal. On October 13, 54 AD, he was poisoned by his wife, Agrippina the Younger, who sought to secure the throne for her son Nero. Claudius’s sudden death marked the end of an era and paved the way for Nero’s controversial reign.

Under Nero

Nero’s early years as emperor indeed saw him surrounded by influential figures such as his mother Agrippina, his tutor Seneca, and the Praetorian Prefect Burrus, who played significant roles in advising and guiding him. However, as Nero matured in his role as emperor, he increasingly sought to assert his independence and rid himself of perceived restraining influences.

The power struggle with his mother Agrippina, who initially wielded considerable influence over him, eventually culminated in her murder, a move that freed Nero from her control and allowed him to consolidate his own authority.

Nero’s reign was marked by a series of controversial actions, including the alleged murders of his wife Claudia Octavia and Britannicus, both children of Claudius. These ruthless acts further solidified Nero’s reputation as a tyrant in the eyes of many historians.

Despite the political intrigues and scandals, Nero showed a keen interest in promoting culture and the arts. He enthusiastically supported athletic games and contests, and he actively participated in various public performances as an actor, poet, musician, and even charioteer. His participation in the Olympic Games in 67 AD stands out as a notable example of his passion for public spectacle and entertainment.

Nero’s reign was also marked by military conflicts, including the Roman-Parthian War overseen by his general Corbulo from 58 to 63 AD, the suppression of Boudica’s Revolt in 60-61 AD by another general, Suetonius Paulinus, and the outbreak of the first Jewish-Roman War towards the end of his rule.

In 64 AD, Nero famously returned to Rome from Antium to oversee relief efforts following the devastating Great Fire of Rome. The destruction caused by the fire provided Nero with an opportunity to embark on ambitious building projects, including the construction of his extravagant Domus Aurea, a vast palace complex known for its opulence and grandeur.

When Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, rebelled against Nero’s rule and garnered support from Galba, a prominent Roman general who would eventually become the next emperor, it marked a turning point in Nero’s reign. Nero was declared a public enemy and condemned to death in absentia, prompting him to flee Rome in a desperate bid to escape the impending threat to his life.

On June 9, 68 AD, faced with the realization that his power was rapidly slipping away and with few allies left, Nero made the fateful decision to take his own life. His suicide marked the tragic end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, which had ruled Rome for nearly a century.