The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (96-192 AD)

The Nerva-Antonine dynasty stands out as one of the most renowned and admired periods in Roman history, often referred to as the “Five Good Emperors” era. This dynasty, comprising Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius, ruled the Roman Empire from 96-192 AD.

The rise of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty followed the assassination of Domitian in 96 AD, which left a power vacuum in the Roman Empire. In response, the Roman Senate elected M. Cocceius Nerva, a respected senator and advisor to Domitian, as the new emperor. Nerva’s selection marked a departure from the autocratic rule of Domitian, as he sought to reconcile with the Senate and restore stability to the Empire.

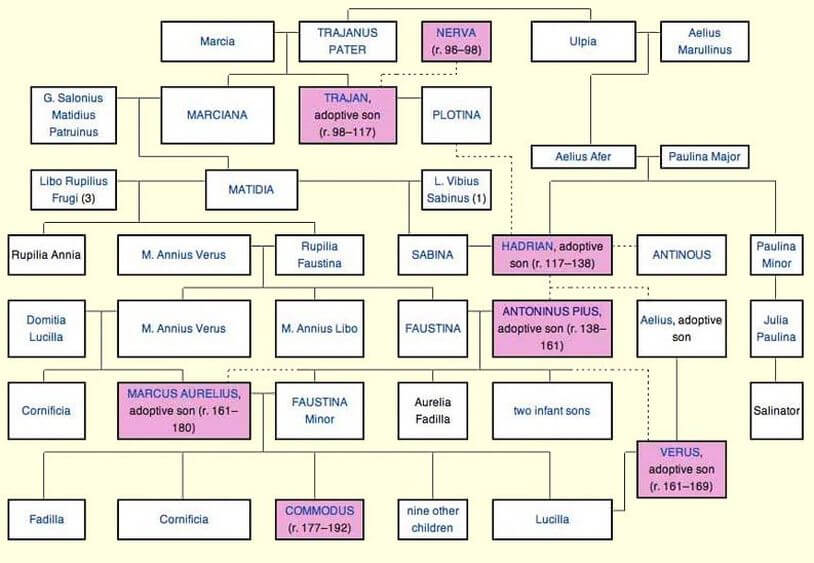

One notable aspect of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty was the adoption of heirs by each emperor, as many of them did not have male heirs of their own. This practice ensured a smooth succession and allowed for continuity in leadership, contributing to the stability and longevity of the dynasty. However, this tradition was broken with Marcus Aurelius, who named his son Commodus as his heir.

Under Nerva

Nerva’s reign, while brief, was indeed marked by significant challenges, particularly in the areas of finance and military control. Economic difficulties and tensions with the Roman Army strained his rule, leading to unrest and a revolt by the Praetorian Guard in 97 AD.

Faced with the Praetorian Guard’s revolt and the need to secure a stable succession, Nerva made the strategic decision to adopt M. Ulpius Traianus, the respected governor of Germania Superior, as his successor. Trajan’s military prowess and popularity made him an ideal choice to restore stability and assert imperial authority.

Despite the challenges Nerva faced during his reign, ancient authors lauded him as a moderate and wise emperor. His willingness to adopt Trajan as his heir demonstrated his commitment to the welfare and continuity of the Roman Empire.

Nerva’s sudden death from natural causes on January 27th, 98 AD, marked the end of his brief but significant tenure as emperor. He was succeeded by Trajan, who would go on to achieve great success and expand the borders of the Roman Empire. Trajan’s reverence for Nerva was evident in his decision to deify him, further cementing Nerva’s place in Roman history as a respected and pivotal figure in the transition of power to the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

Under Trajan

Trajan’s legacy as one of the greatest Roman emperors is well-deserved, as his reign witnessed a series of remarkable achievements and advancements that left an indelible mark on the Roman Empire.

As a military emperor, Trajan oversaw an unprecedented expansion of Roman territory, bringing the empire to its greatest territorial extent by the time of his death. His conquests included the annexation of the Kingdom of Nabataea in 106 AD, which led to the creation of the province of Arabia Petraea, and the famed Dacian Wars of 101-2 AD and 105-6 AD, culminating in the annexation of the Kingdom of Dacia.

One of Trajan’s most significant military campaigns was his successful campaign against the Parthian Empire, which ended with the sack of their capital, Ctesiphon, and the annexation of Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Assyria as Roman provinces. These conquests brought immense wealth and resources to the Roman Empire, further strengthening its power and influence in the region.

In addition to his military achievements, Trajan implemented an extensive building program throughout the empire. Thanks to the newly acquired gold mines in Dacia, Trajan financed ambitious construction projects, including the construction of a new forum in Rome, which came to be known as the Forum of Trajan, and the development of a new harbor called Portus next to Ostia, facilitating maritime trade and enhancing Rome’s economic prosperity.

Furthermore, Trajan implemented innovative social welfare programs aimed at improving the lives of his subjects, demonstrating his concern for the well-being of the Roman populace. His reign is remembered as a period of relative peace, prosperity, and stability, characterized by economic growth, cultural flourishing, and the promotion of Roman values and ideals.

In late 117 AD, while sailing back from the East, Trajan fell ill and died of a stroke in the city of Selinus in Cilicia. He was deified by the Senate and his ashes were laid to rest under Trajan’s Column in his new Forum. He was succeeded by his cousin Hadrian, whom Trajan supposedly adopted on his deathbed according to his wife Plotina.

Under Hadrian

Hadrian’s reign represented a significant departure from the expansionist policies of his predecessor, Trajan. Instead of seeking further territorial conquests, Hadrian focused on consolidating and fortifying the existing borders of the Roman Empire, a strategy aimed at ensuring stability and security.

One of Hadrian’s most renowned achievements in this regard was the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britannia, a monumental defensive barrier designed to protect the Roman province from incursions by northern tribes.

Despite his initial approval by the Roman Senate and army, Hadrian’s reign was marked by tensions with the Senate, exacerbated by his authoritarian tendencies and the execution of four leading senators shortly after his ascension. This rift strained relations between Hadrian and the Senate throughout his rule, underscoring the challenges of governing an empire as vast and diverse as Rome.

Hadrian’s extensive travels throughout the empire, during which he visited nearly every province, showcased his commitment to understanding and managing the diverse needs of his subjects. His building program, which included the reconstruction of the Pantheon in Rome and the restoration of Athens to its former glory, reflected his appreciation for art, culture, and architecture.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt of 132-136 AD, the only major military conflict of Hadrian’s reign, demonstrated the challenges of maintaining control over distant provinces. The revolt, led by the Jewish leader Bar Kokhba, resulted in significant casualties and required a prolonged and costly military campaign to suppress.

Hadrian’s relationship with his favorite, Antinous, remains a subject of fascination and speculation. Antinous’s mysterious drowning in the River Nile led Hadrian to deify him, immortalizing him in art and sculpture throughout the empire and establishing a cult in his honor.

He died on 10th July 138 AD at his villa in Baiae and was succeeded by Antoninus Pius, whom he had adopted that year and in turn had made Antoninus adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Under Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius, known for his epithet “Pius,” ascended to the imperial throne following the reign of Hadrian. His reign is celebrated for its peacefulness and administrative prowess, characterized by stability and prosperity throughout the Roman Empire.

The cognomen “Pius” was bestowed upon Antoninus shortly after he became emperor, reflecting his efforts to honor and uphold the traditions of the Senate and the Roman state. It is believed that he earned this epithet either by securing the deification of Hadrian or by saving senators from potential death during the tumultuous later stages of Hadrian’s reign.

Under Antoninus Pius, the Roman Empire experienced a period of tranquility, with no major military conflicts occurring during his tenure. While he did oversee a successful military campaign in southern Scotland, which led to the construction of the Antonine Wall, his focus remained on maintaining peace and stability throughout the empire.

As an effective administrator, Antoninus left a lasting legacy of prudent governance and fiscal responsibility. He ensured a large surplus in the imperial treasury, facilitating economic prosperity and financial security. Additionally, Antoninus prioritized infrastructure development, improving access to drinking water across the empire and promoting legal conformity and the enfranchisement of freed slaves.

Antoninus Pius’s reign came to an end with his death from illness on March 7th, 161 AD. He was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as co-emperors.

Under Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius, the last of the “Five Good Emperors,” faced significant challenges during his reign, yet he is remembered for his philosophical wisdom and steadfast leadership.

The majority of Marcus Aurelius’s reign was consumed by military campaigns, particularly the Marcomannic Wars from 166-180 AD, fought along the Danube frontier against Germanic tribes. While Marcus Aurelius focused on the defense of the northern borders, his co-emperor Lucius Verus led Roman forces in the East against the Parthians.

During this time, the Antonine Plague, believed to have been brought back by soldiers returning from the East, ravaged the empire, claiming millions of lives. This devastating epidemic further strained the empire’s resources and exacerbated its military challenges.

Marcus Aurelius’s stoic philosophy, exemplified in his private notes known as the “Meditations,” provided him with guidance and strength during these turbulent times. His reflections on Stoicism have inspired countless individuals throughout history, earning him admiration as both a philosopher and a ruler.

Despite the hardships he faced, Marcus Aurelius declined to adopt an heir and instead ruled jointly with his son Commodus from 177 AD. This decision would have significant consequences for the empire, as Commodus’s reign marked a departure from the virtues of his father and the “Five Good Emperors” era.

Marcus Aurelius’s death on March 17th, 180 AD, at Vindobona (modern-day Vienna) while on campaign, marked the end of an era of enlightened rule. He was succeeded by his son Commodus, whose reign would usher in a period of decline and instability in the Roman Empire.

Under Lucius Verus

Lucius Verus, co-emperor alongside Marcus Aurelius, played a significant role in Roman history, particularly through his military campaigns and his reputation in Rome.

Lucius Verus’s reign was defined by his war with Parthia from 161-166 AD, during which Roman forces achieved victory and secured some territorial gains in the East. However, despite the military successes, Lucius Verus gained notoriety in Rome and among soldiers for his indulgent lifestyle characterized by debauchery and opulence, contrasting sharply with the stoic virtues upheld by his co-emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Following the conclusion of the Parthian War, Lucius Verus was involved in the Marcomannic Wars in the northern frontier. However, his active participation was cut short when he fell ill and died in 169 AD, possibly succumbing to the Antonine Plague, which swept through the empire during this time.

Under Commodus

Commodus’s reign marked a stark departure from the principles of his predecessors. While he initially sought to conclude the Marcomannic Wars and maintain peace, his rule gradually devolved into despotism and extravagance.

Unlike the diligent administration of the Empire by the previous Antonine emperors, Commodus showed little interest in governance, preferring to delegate authority to court officials and his Praetorian Prefect. However, as conspiracies and attempted coups threatened his reign, Commodus was compelled to take a more hands-on approach, leading to a consolidation of power that increasingly bordered on tyranny.

Despite his unpopularity among the Senate, Commodus cultivated a strong rapport with the common people, largely through his lavish and extravagant displays, particularly his participation in gladiatorial shows. These spectacles, though popular with the masses, further alienated him from the aristocracy and fueled discontent within the ruling elite.

Commodus’s reign came to a dramatic end with his assassination on December 31st, 192 AD, in a palace plot orchestrated by conspirators. His death marked the demise of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and plunged the Roman Empire into a period of turmoil known as the Year of the Five Emperors, characterized by civil unrest and successive power struggles for control of the empire.