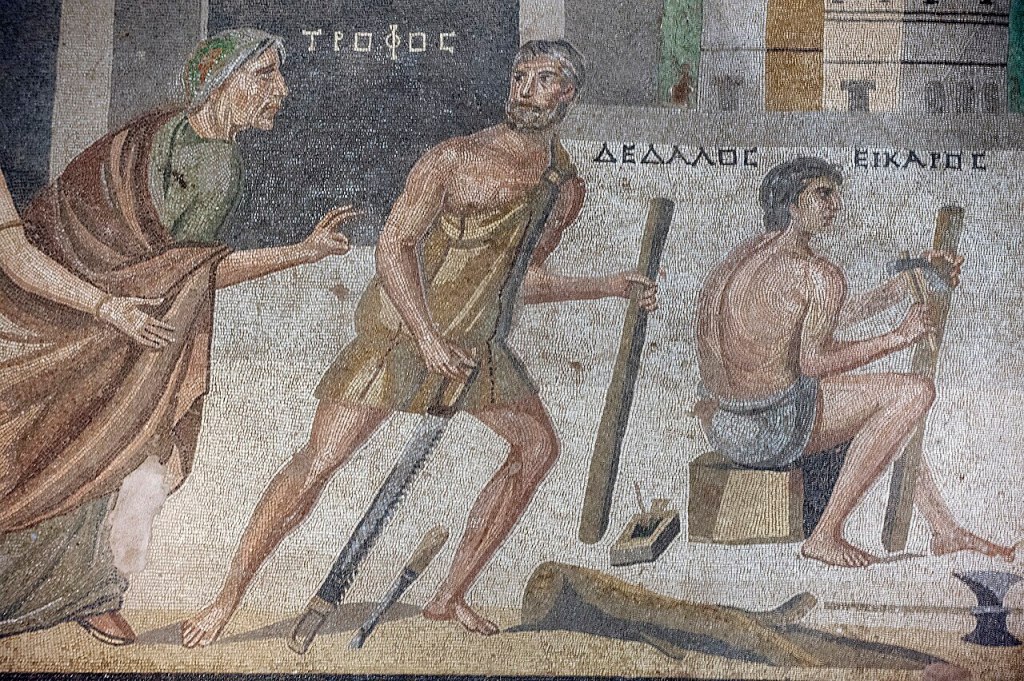

Daedalus

A true architect and sculptor, his creations blurred the line between mortal ability and divine inspiration. From labyrinthine palaces to lifelike statues that seemed to breathe, Daedalus’ reputation as a genius preceded him throughout ancient Greece.

Parents: Metion and Alcippe

Children: Icarus and Iapyx

Crete

The bond between Daedalus and King Minos wasn’t always strained. Initially, their relationship flourished. Daedalus, the ingenious architect, was revered by Minos for his talent. He wasn’t just a craftsman; he was a creator, and his greatest challenge came in the form of the Labyrinth. This wasn’t your ordinary building; it was a sprawling maze, a cunningly designed prison built upon King Minos’ orders. Its purpose? To house the monstrous Minotaur, a creature half-man, half-bull, a terrifying beast that demanded appeasement.

However, the tides of fortune began to turn. There are whispers of different reasons for this discord, but the most well-known story centers around a young woman named Ariadne, the king’s daughter. Legend tells us that Daedalus, for reasons unknown, played a pivotal role in aiding Ariadne. Perhaps he felt sympathy for her plight, or maybe he was swayed by another force entirely. Whatever the reason, Daedalus became instrumental in providing Ariadne with a ball of string, a lifeline for Theseus, the Athenian hero who ventured into the Labyrinth to slay the Minotaur. Armed with this gift and his own courage, Theseus navigated the maze’s treacherous paths, ultimately defeating the beast.

Minos, upon discovering this betrayal, was enraged. Daedalus’ brilliance, once a source of pride, now turned into a bitter reminder of his defiance. The king, blinded by fury, imprisoned both Daedalus and his young son, Icarus, within the very Labyrinth Daedalus himself had constructed. From creator to captive, Daedalus found himself trapped in his own ingenious design, a chilling twist of fate that set the stage for their daring escape attempt.

Flying High

Imprisoned within the very labyrinth he built, Daedalus, the ingenious architect, was faced with a seemingly impossible task – escape. The towering walls of the Labyrinth, designed specifically to be inescapable, now loomed as a constant reminder of his captivity. But Daedalus wasn’t one to give up. Hope flickered within him, fueled by his love for his son, Icarus.

Daedalus, with a mind that could forge marvels from stone and wood, turned his attention to the boundless sky. Escape by land or sea was out of the question. The Cretan guards were vigilant, and the labyrinth’s location made escape by ship an impossibility. That left only one option – the air itself. This wasn’t just thinking outside the box; it was defying gravity itself.

Fueled by desperation and inspiration, Daedalus embarked on a project that would become legend. He meticulously gathered feathers, those light and airy quills that seemed to embody the freedom they sought. Using beeswax, a natural adhesive, he painstakingly attached them to a wooden frame, crafting the first wings the world had ever seen. These weren’t just rudimentary tools; they were symbols of hope, of defying the limitations imposed upon them.

Before taking flight, Daedalus, ever the cautious teacher, drilled a crucial lesson into Icarus’s mind. The wings, he warned, were held together by wax, sensitive to the sun’s scorching heat. Icarus, young and perhaps a little overconfident, listened to his father’s instructions, but the thrill of the unknown, the intoxicating sensation of flight, might cloud his judgment later.

And so, father and son took to the skies. Daedalus, the architect, became Daedalus the aviator, soaring through the air with a marvel of his own creation. For a brief, glorious moment, they were free. They skimmed the waves, leaving behind the prison that had held them captive.

The Fall of Icarus

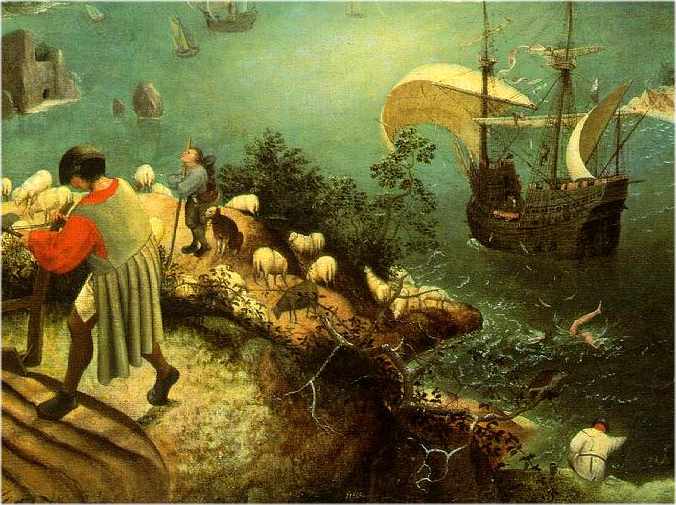

But freedom, especially newfound freedom, can be a heady sensation, and Icarus, young and impulsive, was no match for its intoxicating power. The thrill of flight filled him with a sense of joyous abandon. Daedalus’ warnings about the sun’s heat seemed distant compared to the exhilaration of soaring through the sky. He dipped and soared, flirting with the sun’s brilliance, lured by a sense of god-like power.

Daedalus, watching his son’s reckless joy, felt a surge of dread. He called out, his voice laced with urgency, reminding Icarus of the fragile nature of their escape. But the wind snatched his words away. Icarus, lost in his euphoria, flew ever higher, wings brushing the searing rays of the sun. In that moment of hubris, tragedy struck. The wax, warned Daedalus, was like a captured flame – useful but easily undone. The sun’s heat, relentless and unforgiving, began to melt the wax that held the wings together.

Terror replaced Icarus’s joy. He flailed his arms, but the feathers, once instruments of liberation, now hung limp. A heart-wrenching cry tore from his lips as he plummeted towards the unforgiving sea. Daedalus, his own wings heavy with despair, watched in horror as his son fell, a once-bright flame extinguished in the vast ocean.

The fall of Icarus wasn’t just a physical descent; it was a metaphor for the dangers of unchecked ambition. The Icarian Sea, named after the fallen boy, became a somber reminder of the fleeting nature of human triumph and the ever-present risk of succumbing to one’s desires. The story echoed through the ages, a cautionary tale for all who dared to dream of reaching for the sun.