Roman Currency

Embark on a captivating journey into the heart of the Roman Empire through the lens of their currency. Witness the transformation of money, from cumbersome bronze ingots to the iconic silver denarius. Explore a diverse cast of coins, each with a purpose, from the workhorse denarius to the emperor-adorned sestertius. Uncover how these coins served more than just monetary exchange, acting as powerful propaganda tools showcasing victories, deities, and the emperors themselves. Finally, learn how the very metal used and its quality act as a secret code, revealing the economic and political climate of the Roman Empire.

Join us as we unlock the stories whispered by these coins, transforming them from mere objects into windows into the fascinating world of ancient Rome.

History

Early Republic

The story of Roman currency begins not with the clinking of coins, but with the dusty exchanges of a barter system. Early Romans, prior to the 4th c. BC, relied on directly exchanging goods and services. For larger transactions, they used cumbersome bronze ingots known as aes rude. Imagine the inconvenience of haggling over the value of an uneven lump of metal! This inefficiency spurred the Romans to seek a more standardized system.

Around the 4th c. BC, with trade expanding and the influence of Greek city-states growing, the Romans adopted coinage. Their initial foray was the aes grave, cast bronze pieces featuring simple geometric designs. This marked a significant improvement over the aes rude, offering a more standardized and portable form of exchange. However, the reliance solely on bronze limited the system’s potential for larger transactions and long-distance trade.

The aes signatum emerged in the 3rd c. BC, representing a transitional phase. These cast bronze pieces still lacked the precision of struck coins, but they incorporated stamped designs and weight standards. This innovation hints at a growing awareness of the benefits of standardized coinage.

The influence of Greek city-states, particularly those in Southern Italy, played a crucial role in shaping early Roman currency. These Greek colonies had adopted coinage earlier, and their practices heavily influenced the Romans. The style and denominations of some early Roman coins, particularly the didrachm (a two-drachm coin), bear a striking resemblance to their Greek counterparts.

Obv: Helmeted head of beardless Mars; behind, club. Rev: Horse galloping; above, club; below, ROMA. (c) VCoins

The introduction of silver coins marked a turning point in early Roman currency. These silver issues, resembling contemporary Greek drachms, were initially worth two drachms and typically displayed the legend “ROMANO” (later evolving to “ROMA”). Their introduction suggests a growing need for a higher-value coin to facilitate trade and military expansion.

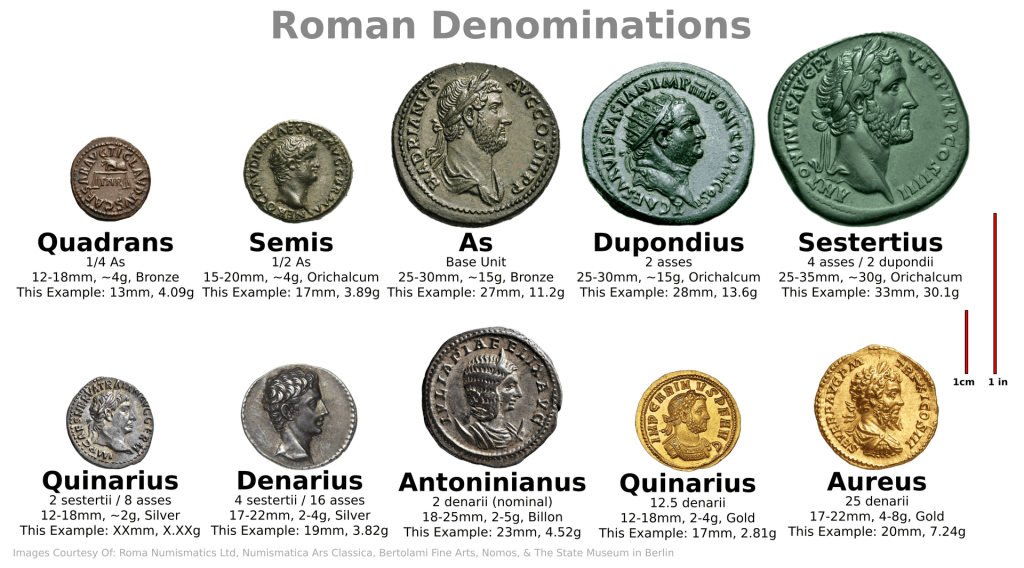

The year 268 BC saw the official minting of the denarius, a high-quality silver coin destined to become the backbone of the Roman monetary system for centuries. Initially valued at ten bronze asses, the denarius displayed a variety of imagery, including Roman deities, consuls, and military victories. This shift towards a reliable silver coinage symbolized Rome’s growing economic and political power.

Obv: Helmeted head of Roma. Rev: Dioscuri galloping; below, ROMA.

RRC 50/2. British Museum.

Early Roman currency faced its share of challenges. The value of bronze coins fluctuated due to changes in the weight and metal content. Additionally, the reliance on bronze for smaller transactions limited practicality for larger purchases. These issues would pave the way for further reforms and the diversification of the Roman monetary system in the centuries to come.

Late Republic into Empire

As the Roman Republic transitioned into the Empire, its coinage system continued to evolve, reflecting the changing economic, political, and artistic landscape.

For centuries, the denarius remained the workhorse of the Roman monetary system. Its silver content remained relatively stable, and its designs continued to showcase Roman deities, victorious generals, and important events. This consistency fostered trust and facilitated trade throughout the expanding empire.

Obv: CAESAR AVGVSTVS DIVI F PATER PATRIAE: Head of Augustus, laureate.

Rev: ROM ET AVG: Altar highly decorated with corona civica, laurels, and nude male figures; Victories flanking.

RIC I, Augustus 231A. British Museum.

While the denarius dominated larger transactions, a new player emerged for everyday use: the sestertius. Originally a large bronze coin worth a quarter of a denarius, its value fluctuated over time. However, it remained a vital component of the system, often featuring portraits of emperors and commemorating significant events. Imagine a sestertius celebrating the construction of a new aqueduct, bringing fresh water to the citizens of Rome.

The dupondius, a smaller bronze coin half the value of a sestertius, continued to circulate and the as, the most basic unit, remained in use for everyday purchases throughout the Republic and into the early Empire.

Obv: IMP CAES VESPASIAN AVG COS III: Head of Vespasian, radiate.

Rev: CONCORDIA AVGVSTI S C: Concordia, seated left, holding patera and cornucopiae.

RIC II, Vespasian 266. British Museum.

Initially reserved for large payments or imperial gifts, the prestigious gold aureus became more common under the Empire. It often displayed the emperor’s image and served as a potent symbol of his authority and wealth. Imagine an aureus showcasing a triumphant emperor, solidifying his claim to power.

As the Empire faced economic challenges, the silver content of the denarius began to decline (debasement). This decline is often linked to the reign of Nero in the 1st c. AD. While the size and design of the coin remained similar, the diminishing silver content weakened its value and disrupted trade. Over time, other denominations also experienced debasement, reflecting the empire’s economic struggles.

Obv: HADRIANVS AVGVST: Head of Hadrian, laureate.

Rev: COS // III (in exergue): She-wolf and twins.

RIC II, Hadrian 708. British Museum.

To meet the growing needs of a vast empire, regional mints were established alongside the central mint in Rome. These regional mints produced coins with varying qualities and designs, reflecting the economic conditions and artistic styles of their respective locations. Studying these regional variations offers valuable insights into the diverse experiences within the Roman Empire.

The 3rd c. AD witnessed a period of political and economic turmoil within the Roman Empire. This instability manifested in the drastic debasement of coinage. Silver content plummeted, and even bronze coins were often mixed with cheaper metals. This decline in quality ultimately contributed to the weakening of the Roman monetary system.

The story of Roman currency after the early Republic showcases the dynamic nature of money and its close relationship to the empire’s political and economic fortunes. The denarius maintained its prominence for centuries, while other denominations like the sestertius gained importance. The introduction of the aureus and the rise of regional mints further diversified the system. However, the debasement of coins during times of hardship ultimately contributed to the weakening of the Roman monetary system, reflecting the broader decline of the empire itself. By studying Roman currency over time, we gain a deeper understanding of the economic and political forces that shaped this powerful civilization.