The Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC)

Also referred to as the Roman Monarchy or the Regal Period, it was the earliest period of Roman history, marked by the legendary founding of the city by Romulus on the Palatine hill in 753 BC.

Little is certain about the Kingdom’s history, as no records and few inscriptions from the time of the kings survive. Accounts of this period written during the Republic and the Empire are thought to be based on oral tradition. The Regal Period came to an end with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 BC.

For Rome’s foundation myth see Romulus & Remus.

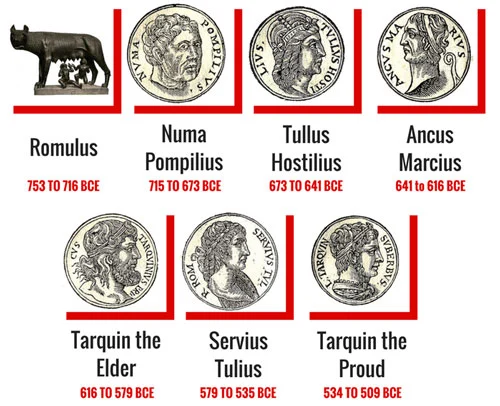

During the Roman Kingdom, seven kings ruled the city of Rome: Romulus (753-716 BC), Numa Pompilius (715-673 BC), Tullus Hostilius (673-641 BC), Ancus Marcius (641-616 BC), Tarquinius Priscus (616-579 BC), Servius Tullius (578-535 BC), and Tarquinius Superbus (535-509 BC).

With the exception of Romulus, the kings were elected by the people of Rome to serve for life, without relying on military force to gain or keep the throne. The insignia of the kings of Rome included twelve lictors wielding the fasces bearing axes, the right to sit upon a Curule chair, the purple Toga Picta, red shoes, and a white diadem around the head.

Romulus

After killing his brother Remus, Romulus began constructing the city on the Palatine Hill. He adopted an inclusive policy, permitting men of all classes, including slaves and freemen without distinction, to become citizens of Rome. Credited with establishing the city’s religious, legal, and political institutions, Romulus played a pivotal role in the formation of the Roman Kingdom. He convened a council of the citizenry to determine the government, leading to the establishment of the senate as an advisory council consisting of 100 of the most noble men, known as patres, whose descendants became the patricians.

To assert authority, Romulus surrounded himself with attendants, notably the twelve lictors. He organized the populace into three divisions of horsemen called centuries: the Ramnes (Romans), the Tities (after the Sabine king), and the Luceres (Etruscans). Additionally, Romulus divided the population into 30 curiae, named after 30 Sabine women who had intervened to end the war between Romulus and Tatius. These curiae formed the voting units in the popular assembly, the Comitia Curiata.

Romulus, a central figure in Roman history, orchestrated the infamous incident known as the Rape of the Sabine women. Seeking wives for his citizens, Romulus invited the neighbouring Sabine tribe to a festival in Rome, during which Roman men abducted young women from among the attendees. This act led to war when Romulus refused to return the captives. Despite three unsuccessful attempts by the Sabines to invade Rome, the conflict came to a turning point during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius, where the abducted women intervened to end the hostilities.

Following this, Romulus and the Sabine king Titus Tatius shared the throne, uniting their peoples under a joint kingdom. In addition to the war with the Sabines, Romulus also waged battles against the Fidenates and Veientes, solidifying his role as a warrior king in Roman legend.

Romulus, the legendary founder and first king of Rome, ruled for thirty-seven years before his mysterious disappearance at the age of fifty-four. According to myth, while reviewing his troops on the Campus Martius, Romulus vanished in a whirlwind, ascending to Mount Olympus where he was deified. Initially accepted by the public, rumors soon surfaced, suggesting foul play by the patricians, including theories of murder and dismemberment. However, these suspicions were dispelled when an esteemed nobleman testified to having received a vision from Romulus, affirming his divine status as Quirinus.

Romulus became not only one of the three major gods of Rome but also the embodiment of the city itself. A replica of Romulus’ humble hut remained preserved in the heart of Rome until the decline of the Roman Empire, symbolizing the enduring legacy of its mythical founder.

Numa Pompilius

After the interregnum following Romulus’ death, Rome was governed by ten successive interreges chosen from the senate for a year. Amid popular pressure, the Senate selected Numa Pompilius, a Sabine known for his justice and piety, to succeed Romulus. Numa’s reign ushered in an era of peace and religious reform. He erected a new temple to Janus and, having secured peace with Rome’s neighbors, ceremonially closed its doors to signify a time of tranquility, a state that endured for the duration of his reign.

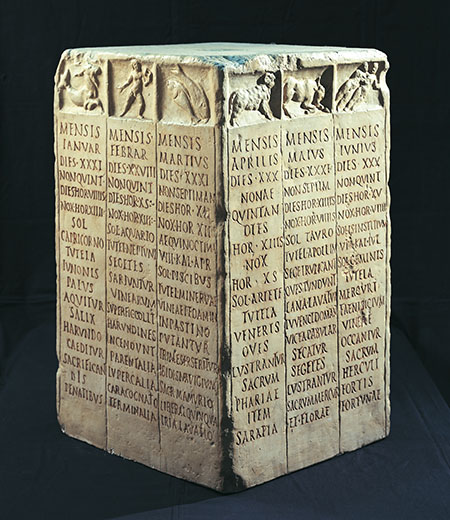

Numa established several religious institutions, including the Vestal Virgins, the Salii, and the flamines for Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. Additionally, he formalized the office and duties of the Pontifex Maximus. Numa’s reign of 43 years also saw significant reforms to the Roman calendar, aligning it with the solar and lunar cycles and introducing the months of January and February to create a twelve-month calendar.

Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius, unlike his predecessor Numa, was characterized by his bellicose nature and disregard for religious matters. He engaged in numerous military campaigns against Alba Longa, Fidenae, Veii, and the Sabines. Under his rule, Alba Longa was razed to the ground, and its inhabitants were assimilated into Rome. Tullus is credited with the construction of the Curia Hostilia, a new seat for the Senate, which endured for 562 years following his death. His reign lasted for 31 years, marked by military conquests and the consolidation of power in Rome.

Ancus Marcius

Following the reign of Tullus Hostilius, known for his military exploits, the Romans turned to a more peaceful and religious leader in the form of Ancus Marcius, the grandson of Numa Pompilius. Ancus, like his grandfather, prioritized defense over expansion and engaged in wars only to protect Rome’s territory. He notably erected Rome’s first prison on the Capitoline Hill and fortified the Janiculum Hill on the western bank, enhancing Rome’s defensive capabilities.

Ancus also undertook infrastructure projects, including the construction of Rome’s first bridge across the Tiber River and the establishment of the port of Ostia on the Tyrrhenian Sea, along with Rome’s first salt works near the port. After a reign of 25 years, marked by peace and development, Ancus Marcius died a natural death, bringing an end to the era of Rome’s Latin-Sabine kings.

Obv: ANCVS: Head of Ancus Marcius, lituus behind.

Rev: PHILIPPVS AQVA MAR: equestrian statue on 5 arches of aqueduct (Aqua Marcia). (c) Johny Sysel

Tarquinius Priscus

L. Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of Rome and the first of Etruscan origin, arrived in Rome as an immigrant and rose to prominence, earning the favor of Ancus Marcius, who adopted him as his son. Upon ascending the throne, Tarquinius waged successful wars against the Sabines and Etruscans, expanding the territory of Rome and bringing substantial wealth to the city. To accommodate the growing population, he initiated the settlement of the Aventine and Caelian hills.

One of his significant reforms was the expansion of the Senate by adding one hundred new members from the conquered Etruscan tribes, doubling the total number of senators to two hundred. Utilizing the acquired treasures, Tarquinius embarked on ambitious construction projects, including the renowned Cloaca Maxima, Rome’s great sewer system, which drained the marshy terrain between the Seven Hills, and the initial development of the Roman Forum, laying the foundation for the city’s central hub of political, social, and commercial activity.

Priscus embarked on numerous monumental building projects, leaving a lasting legacy in Rome’s architectural landscape. Among these ventures was the construction of the city’s inaugural bridge, the Pons Sublicius, which facilitated communication and commerce across the Tiber River. Notably, he commissioned the iconic Circus Maximus, an immense stadium renowned for hosting exhilarating chariot races and other grand spectacles that captivated the Roman populace. Additionally, Priscus initiated the ambitious endeavor of erecting the temple dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus atop the Capitoline Hill, symbolizing Rome’s devotion to its principal deity. Regrettably, before the completion of these endeavors, his reign was cut short by his untimely demise, allegedly at the hands of a son of Ancus Marcius, marking the end of his thirty-eight-year reign as king.

Servius Tullius

Priscus’s son-in-law, Servius Tullius, assumed the throne following his predecessor’s demise, heralding a new era in Rome’s monarchy. Despite his humble origins as the son of a slave, Servius demonstrated formidable leadership qualities and military prowess akin to his illustrious predecessor. He continued the legacy of expansion and conquest, achieving notable victories against the Etruscans and leveraging the spoils of war to fortify Rome’s defenses. Notably, Servius embarked on a groundbreaking architectural project by erecting the first defensive wall encircling the Seven Hills of Rome, known as the pomerium, thereby enhancing the city’s security and laying the foundation for its future growth and prosperity.

Servius Tullius implemented groundbreaking reforms that reshaped the socio-political landscape of Rome, marking a significant departure from traditional governance practices. His introduction of the first census revolutionized the classification of citizens based on economic status, laying the groundwork for a more structured and inclusive political system. By organizing the population into distinct classes and assemblies, such as the Centuriate Assembly and the Tribal Assembly, Servius Tullius aimed to streamline governance and ensure broader representation across societal strata.

However, his reforms stirred both admiration and controversy, as they shifted the balance of power towards the elite while also appealing to the plebeian class through populist measures. Despite his initial support from the patricians, Servius’s overtures to the plebeians ultimately led to resentment and dissent among the aristocracy. His reign, characterized by socio-political upheaval and class tensions, came to a tumultuous end with his assassination orchestrated by his own daughter Tullia and her husband L. Tarquinius Superbus, signaling the onset of a turbulent period in Roman history.

Tarquinius Superbus

The reign of L. Tarquinius Superbus, the seventh and final king of Rome, was marked by a combination of military conquests and ambitious public projects. Despite his efforts to expand Rome’s territory through wars against neighboring peoples and securing its leadership among the Latin cities, his rule was marred by a heavy-handed approach to governance characterized by violence and intimidation.

While Tarquinius Superbus oversaw significant infrastructure developments, including the completion of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus and enhancements to the Cloaca Maxima and Circus Maximus, his disregard for Roman customs and the authority of the Senate earned him a reputation for tyranny and despotism. His actions alienated both the patrician and plebeian classes, leading to widespread discontent and unrest within Rome.

Ultimately, Tarquinius Superbus’s oppressive rule and disdain for traditional governance norms precipitated his downfall, culminating in a popular uprising that resulted in his expulsion from Rome and the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 BC. Despite his ambitious projects and military achievements, his legacy is overshadowed by his autocratic tendencies and the pivotal role he played in the transition from monarchy to republicanism in ancient Rome.

The rape of Lucretia by Sextus Tarquinius served as the catalyst for the downfall of the Tarquinii dynasty and the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 BC. Lucretia’s tragic fate galvanized public outrage and led to a popular uprising led by figures such as L. Junius Brutus, L. Tarquinius Collatinus, P. Valerius Poplicola, and Sp. Lucretius Tricipitinus. Their efforts culminated in the expulsion of Tarquinius and his family from Rome, symbolizing the rejection of monarchical rule and the oppressive reign of the Tarquinii.

The revulsion towards Tarquin’s tyrannical regime was so profound that the very title of king, rex, acquired a negative connotation in the Latin language, persisting until the decline of the Roman Empire. Julius Caesar, cognizant of the public’s aversion to kingship, notably eschewed the title of rex, and fears of his potential aspirations for kingship contributed to the conspiratorial atmosphere surrounding his assassination.

With the ascension of Brutus and Collatinus as Rome’s first consuls, the Roman Republic was born, ushering in a new era of governance characterized by shared authority and representation. Over the next five centuries, the Roman Republic would experience remarkable expansion and influence, shaping the course of Western civilization and establishing Rome as a dominant power in the Mediterranean Basin.