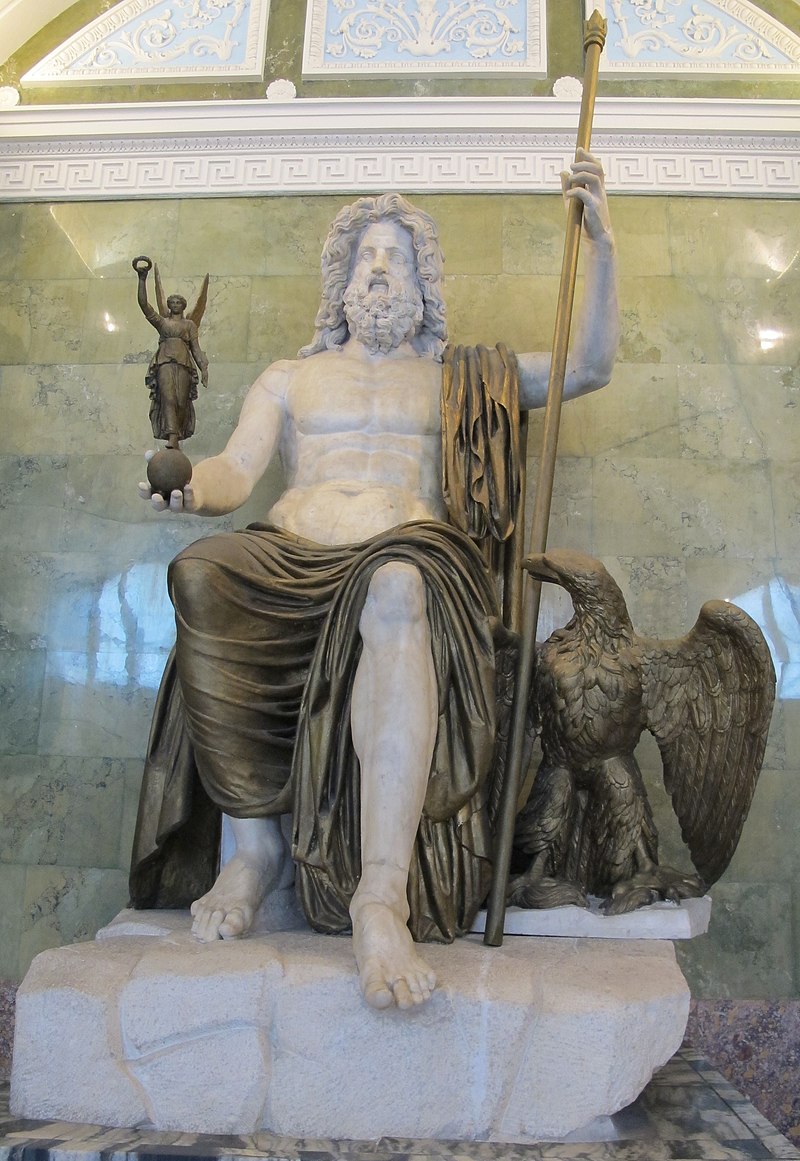

Jupiter

Jupiter, the Roman king of the gods, wielded the power of the sky. His booming voice echoed in thunder, and his rage manifested in lightning strikes. As the head of the Roman pantheon, he commanded immense respect and authority.

Residence: Rome

Symbols: Lightning blot, eagle, oak tree

Parents: Saturn and Ops

Siblings: Ceres, Juno, Neptune, Pluto, Vesta

Consort: Juno

Children: Bellona, Juventas, Mars, Minerva, Vulcan

Greek equivalent: Zeus

Other Names: Jove

Jupiter reigned supreme throughout the Republic and Imperial eras. He wasn’t just a powerful deity; he was the cornerstone of Roman state religion, his authority unwavering until the rise of Christianity. Mythology tells of Jupiter’s pact with Numa Pompilius, the wise second king of Rome. Together, they established the core principles of Roman religion, including proper offerings and sacrifices to appease the gods and ensure Rome’s prosperity. This divine partnership cemented Jupiter’s position as the ultimate authority, not just in the heavens, but in the very soul of the Roman state.

As the sky-god, his gaze held immense power. He served as a divine witness to oaths, a constant reminder of the sacred trust upon which justice and good government depended. Many of his most important functions centered on the Capitoline Hill, the heart of Rome. Here, within the revered Capitoline Triad, Jupiter stood as the central guardian of the state, flanked by Juno, the queen, and Minerva, the goddess of wisdom. The mighty oak, a symbol of strength and stability, served as his sacred tree.

Jupiter Column

The Jupiter Column was a monument prevalent in the Roman province of Germania during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. Typically found near Roman settlements or villas, these occasional visitors to Gaul and Britain were more than just decorative pillars. Their bases, called Viergötterstein, depicted four important Roman gods: Juno, Minerva, Mercury, and Hercules. A midsection carving, the Wochengötterstein, presented the personifications of the seven days of the week. Finally, the column itself, often adorned with a scale pattern, stood tall. These fascinating structures served a dual purpose. Primarily, they were religious expressions, highlighting the importance of Jupiter, the king of the Roman gods. Secondly, they functioned as historical markers, offering a glimpse into the lives, political leanings, and religious beliefs of the Romans who built them.

Numa Pompilius

During a critical time in early Rome, a period of bad weather threatened the harvest. King Numa Pompilius, determined to save the crops, devised a daring plan to seek advice from Jupiter himself. He employed the help of Picus and Faunus, local deities he had cleverly incapacitated with wine. These lesser gods then summoned Jupiter, who was compelled to descend to the Aventine Hill.

Numa, a cunning negotiator, skillfully deflected Jupiter’s demands for human sacrifices. Instead, he proposed a series of alternative offerings – an onion bulb, hairs, and a fish. Impressed by Numa’s resourcefulness, Jupiter agreed to share his knowledge on averting lightning strikes. Furthermore, he promised a symbol of Rome’s future dominion (imperium) at sunrise the following day.

True to his word, Jupiter sent a clear sign. With a series of three thunderous cracks, a shield materialized from the heavens. This shield, lacking sharp angles, was named the Ancile, for its shape resembled the Latin word for “little ring.” Recognizing the Ancile’s significance as a safeguard for Rome’s power, Numa had eleven identical copies crafted to protect the original. He entrusted these shields to the Salii, a band of warrior-priests, ensuring the Ancile’s safekeeping.

Art

LVR RomerMuseum.

Bonn Landesmuseum

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

Vatican Museum.