Heracles

Heracles, renowned for his immense strength, was not only the greatest Greek hero but also one who faced incredible challenges. Upon his death, Heracles received the ultimate honor – a place among the gods on Mount Olympus.

He became the imposing gatekeeper of heaven, his strength now guarding the realm of the gods. He was also recognized as the god of heroic endeavors, forever an inspiration for those who dared to face great challenges. Additionally, he was seen as an averter of evil, a symbol of hope against monstrous threats.

Residence: Mount Olympus

Symbols: Club, Nemean Lion, bow and arrows

Parents: Zeus and Alcmene

Siblings: Aeacus, Angelos, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Ilithyia, Enyo, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses and the Moirae

Consort: Hebe

Children: Telephus, Hyllus, Tlepolemus, Alexiares and Anicetus

Roman equivalent: Hercules

Birth

Heracles’ origin story is steeped in divine trickery. Zeus, known for his infidelity, seduced Alcmene by disguising himself as her husband, Amphitryon, just returned from war. This resulted in a rare phenomenon known as heteropaternal superfecundation, where Alcmene conceived twins fathered by different men: Heracles by Zeus and a mortal son by Amphitryon.

On the very night Heracles and Iphicles were to be born, Hera, furious over Zeus’ betrayal, raced to manipulate the situation. She tricked Zeus into swearing an oath that ensured another descendant of Perseus, not Heracles, would become king. Meanwhile, trapped in agony, Alcmene endured the delayed birth as Hera forced Ilithyia, the goddess of childbirth, to stall the process. Hera even caused Eurystheus’ premature birth to solidify his claim to the throne. However, a clever lie from Alcmene’s servant, Galanthis, tricked Hera, allowing Heracles and Iphicles to finally enter the world.

Fearful of Hera’s vengeance, Alcmene exposed the infant Heracles. However, the goddess Athena, protector of heroes, intervened. She retrieved the baby and brought him to Hera, who, unaware of his true identity, nursed him out of pity. Heracles’ powerful suckling caused Hera pain, and she pushed him away, spraying her divine milk across the sky, which formed the Milky Way. This act inadvertently bestowed supernatural powers upon Heracles. Athena then returned the infant to his parents, where he was raised.

Though renamed Heracles, the shadow of Hera’s wrath loomed large. Hera, relentless in her fury, sent two gigantic serpents slithering into the children’s chamber. Iphicles cried from fear, but the eight-month-old Heracles, in a display of phenomenal strength, grabbed a snake in each hand and strangled them. Found by his nurse playing with the lifeless serpents as if they were toys, Amphitryon, astonished, sent for the seer Tiresias. Tiresias, gazing into the future, prophesied an unusual destiny for the boy, foretelling Heracles would vanquish numerous monsters.

Youth

Driven mad by Hera’s vengeful curse, Heracles committed a horrific act, slaying his beloved wife Megara and their children. Devastated by the realization of his actions, Heracles sought answers at the Oracle of Delphi. Unbeknownst to him, the Oracle, possibly influenced by Hera, directed him to serve King Eurystheus for ten years and perform any task Eurystheus required of him. This servitude, known as the Twelve Labors, became a chance for Heracles to atone for his crimes and prove himself a hero once more.

The Twelve Labors

Despite facing seemingly insurmountable challenges, Heracles conquered each task of the Labors with his characteristic strength and ingenuity. However, Eurystheus, ever jealous of Heracles’ prowess, refused to accept two of his triumphs. He claimed the cleansing of the Augean Stables wasn’t valid because Heracles planned to receive payment, a minor technicality. Eurystheus also disregarded the slaying of the Hydra because Heracles’ nephew, Iolaus, assisted in burning the multiplying heads. Grasping at straws, Eurystheus added two more labors: fetching the Golden Apples of Hesperides and capturing the fearsome Cerberus. With his usual determination, Heracles successfully completed these additional tasks, bringing the total count to the fabled twelve.

(1) The Nemean Lion

The Nemean Lion, a monstrous beast with an impenetrable hide, had become a plague upon the land. King Eurystheus, eager to test the strength of Heracles, sent him to vanquish this seemingly unstoppable foe. Heracles, undaunted, tracked the lion to its lair. A suffocating stench filled the cavern as Heracles lunged, the beast’s roar echoing through the darkness. In a brutal struggle, Heracles emerged victorious, forever marking his triumph with the impenetrable pelt of the Nemean Lion.

(2) The Lernaean Hydra

The Lernaean Hydra, a monstrous serpent with nine regenerating heads, posed an almost insurmountable challenge. With each severed head, two more sprouted, making victory seem impossible. Undeterred, Heracles charged into the swamp, his club flashing in the sunlight. But for every head he cleaved, two more erupted, leaving him frustrated. Realizing the single strategy wouldn’t work, Heracles, with a mighty roar, called upon his nephew Iolaus. Together, they devised a cunning plan. As Heracles wrestled the central head, its venomous breath scorching the air, Iolaus charged in, searing the severed necks with flaming torches. The stench of burning flesh filled the swamp, smoke billowing into the sky. Finally, with Heracles’ strength and Iolaus’ quick thinking, the monstrous Hydra was vanquished. Victorious, Heracles dipped his arrows in the creature’s deadly poison, forever marking his triumph.

(3) The Ceryneian Hind

Respectful of the deer’s divine connection, Heracles avoided harming the creature, focusing instead on capturing it alive. This proved an immense challenge, a year-long chase that stretched across Greece. Finally, near Mount Artemision in Arcadia, he managed to corner the exhausted animal. Enraged by the capture of her sacred creature, Artemis confronted Heracles. The mighty hero, ever persuasive, explained the task set before him by Eurystheus and the necessity of capturing the deer unharmed. Impressed by his respect and perseverance, Artemis allowed Heracles to borrow the creature, but not to keep it.

(4) The Erymanthian Boar

A monstrous boar, with fur like a tangled thicket and tusks that foamed with rage, terrorized the farmlands of Psophis in western Arcadia. Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, fearing Heracles’ growing power, tasked the hero with capturing the beast alive. Heracles, ever the unwavering demigod, tracked the boar through the treacherous winter snows of Mount Erymanthos. After a relentless chase, he ensnared the boar in a massive net and brought it back, snorting and furious, to a terrified Eurystheus. The craven king, fearing the creature’s wrath, cowered in a buried pithos jar, a sight that would become a source of mockery for years to come.

(5) The Augean Stables

King Augeas of Elis, notorious for his stubborn pride, owned a herd of 3,000 divinely blessed cattle. These weren’t ordinary beasts; their immortality ensured an unceasing production of waste. For thirty years, the filth accumulated within Augeas’ stables, a fetid testament to his neglect. Eurystheus, ever the cunning tormentor, tasked Heracles with cleaning this Augean mess. Undeterred by the stench and sheer volume, the mighty demigod devised a brilliant plan. He diverted the courses of the mighty Alpheus and Peneus rivers, channeling their torrents through the stables. In a raging current, the years of accumulated filth were swept away, leaving behind a pristine haven for the bewildered cattle.

(6) The Stymphalian Birds

These monstrous, man-eating birds plagued Lake Stymphalis in Arcadia. Their feathers were like sharpened arrows, and their droppings poisoned the land. Heracles, the hero known for his strength and ingenuity, was tasked with clearing this avian infestation.

Heracles devised a clever strategy. He used a giant rattle, crafted from bronze, to startle the birds from their hiding places in the dense reeds around the lake. The sudden clamor sent them into a frenzy, filling the sky with a whirlwind of feathers and beaks. Heracles, seizing his opportunity, unleashed a volley of arrows tipped with the deadly Hydra’s venom. Any birds that escaped his arrows found themselves snagged in the thick, specially-treated clappers he’d hung around the lake.

Though many fell, some of the birds managed to escape the poisonous hail. They fled to a distant island in the Euxine Sea, where they established a new home. Unfortunately for them, their reign of terror wasn’t over. They would later encounter the legendary Argonauts on their epic voyage.

(7) The Cretan Bull

A magnificent bull, a gift from the sea god Poseidon, emerged from the waves onto the shores of Crete. King Minos, ruler of the island, was awestruck by the creature’s beauty. However, fate had a crueler twist in store. Queen Pasiphaë, Minos’ wife, became consumed by an unnatural desire for the bull. With the ingenious aid of the craftsman Daedalus, she enacted a horrific plan. Daedalus constructed a hollow wooden cow, so lifelike it deceived the bull. Pasiphaë concealed herself within this macabre creation, and from this unholy union, a monstrous offspring was born: the Minotaur, a creature with a man’s body and a bull’s head.

Heracles, the legendary hero, arrived on Crete on a seemingly simple mission: capture the Cretan Bull. Though magnificent, the beast had become a symbol of divine wrath, rampaging across the island. Heracles, with his unmatched strength, subdued the bull and brought it back under control. However, in a surprising turn, he released the creature. The freed bull, driven by a wild spirit, eventually wandered to the Athenian town of Marathon, where it terrorized the land. There, it met its final demise at the hands of another legendary hero, Theseus.

(8) The Mares of Diomedes

King Diomedes, a savage ruler of the Bistones in Thrace, harbored a dark secret. His prized mares, renowned for their strength and fiery temper, weren’t fed grain or hay. Their sustenance was far more gruesome – human flesh. Heracles, the mighty demigod, was tasked with capturing these monstrous steeds. He journeyed to Thrace and, with his immense strength, overpowered Diomedes and his men. He successfully subdued the mares, their eyes blazing with an unnatural hunger. Trusting his young companion, Abderus, to watch over them, Heracles confronted the barbaric king.

Tragedy struck upon Heracles’ return. He found Abderus torn to pieces, devoured by the very beasts he had entrusted to his care. Grief and rage surged through the demigod. In a moment of fierce retribution, he fed Diomedes himself to his ravenous mares. The taste of their own master seemed to satiate their unnatural craving, allowing Heracles to finally tame and control them.

(9) The Belt of Hippolyta

Hippolyta, the formidable queen of the Amazons, possessed a wondrous girdle – a gift from Ares, the god of war. Woven with magic, it symbolized her power and prowess. Heracles, the famed demigod, arrived on their shores, tasked with retrieving this prized possession for King Eurystheus’ daughter, Admete.

Initially, the encounter seemed amicable. Hippolyta, impressed by Heracles’ strength and reputation, was willing to relinquish the girdle. However, the ever-devious Hera intervened. Disguised as an Amazon, she sowed discord among the warriors, whispering rumors of abduction. The Amazons, fiercely protective of their queen, erupted in a frenzy. A fierce battle ensued. In the chaotic clash, tragedy struck. Hippolyta, caught in the crossfire, fell by Heracles’ hand. Grief and urgency surged through him. He retrieved the girdle, fought his way back to his ship, and sailed away, leaving behind a battlefield steeped in sorrow and misunderstanding.

(10) The Cattle of Geryon

Geryon, a monstrous giant with three bodies, four wings, and a fearsome presence, resided on the mythical island of Erytheia. This island lay at the very edge of the world, nestled beside the encircling river Oceanus. Geryon’s prized possession was a herd of magnificent cattle, their hides shimmering red, as if perpetually bathed in the fiery glow of the sunset. Eurystheus, ever tormenting Heracles, tasked the hero with retrieving these extraordinary beasts.

Heracles, known for his daring exploits, embarked on a seemingly impossible journey. He bartered with the sun god Helios, borrowing his golden cup-boat, a vessel that could traverse the celestial waters of Oceanus. Upon reaching Erytheia, he faced a series of challenges. First, he slew Eurytion, the two-headed herder who guarded the cattle with unwavering loyalty. Then, in a ferocious battle, he overpowered Orthrus, the monstrous two-headed guard dog with a venomous bite. Finally, Heracles confronted Geryon himself. In a clash of titans, the hero’s strength and determination prevailed, and the three-bodied giant fell.

Victorious, Heracles herded the cattle onto the golden boat and embarked on the long journey back to the Greek Peloponnese. The retrieval of these magnificent creatures marked another triumph in the hero’s legendary labors.

(11) The Golden Apples of the Hesperides

The Hesperides, nymphs cloaked in the golden light of sunsets, were the daughters of either Nyx, the personification of night, or Atlas, the titan who held the heavens on his shoulders. Entrusted to their care was a wondrous tree, a gift from Gaia, the Earth Mother, to Hera on her wedding day. Its branches bore golden apples, rumored to grant immortality. Guarding this celestial bounty was Ladon, a fearsome dragon with a hundred watchful heads.

Heracles, tasked by the ever-scheming Eurystheus to retrieve these legendary apples, embarked on a perilous journey. He finally reached the Hesperides’ garden, a place of breathtaking beauty bathed in the golden hues of twilight. There, he confronted the mighty Ladon. In a fierce battle, Heracles’ strength and cunning prevailed. He slew the dragon, its hundred watchful eyes closing forever.

However, obtaining the apples proved even more challenging. The Hesperides, wary of strangers, refused to relinquish them. Here, Heracles’ wit came into play. He tricked Atlas, Ladon’s father, into retrieving the apples by offering to hold the heavens for a moment. Once Atlas had the apples, Heracles cleverly refused to take back the burden, forcing Atlas to return the fruit himself. With the golden apples in hand, Heracles returned to Eurystheus. However, the apples were not meant for a mortal king. Under the watchful eye of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, the golden apples were eventually returned to the Hesperides, ensuring their continued safekeeping.

(12) Cerberus

Cerberus, a monstrous hound with three ferocious heads, fangs dripping venom, and a serpent for a tail, stood guard at the gates of the Underworld. This fearsome beast, loyal to the god Hades, prevented the souls of the dead from escaping and the living from entering. Eurystheus, ever-cruel, tasked Heracles with capturing this terrifying guardian and bringing him to the surface world.

Undeterred by the seemingly impossible feat, Heracles ventured into the depths of the Underworld. There, he encountered Persephone, queen of the Underworld. With her blessing, secured through his diplomacy or perhaps the pity she felt for his plight (depending on the teller of the tale), Heracles was allowed to face Cerberus. A brutal battle ensued. Despite Cerberus’ monstrous size and venomous bite, Heracles’ immense strength and unwavering determination prevailed. He overpowered the three-headed hound, but unlike other foes, did not slay him.

Heracles then emerged from the Underworld, Cerberus snarling and snapping at his heels. The sight of the monstrous hound terrified Eurystheus, who cowered in fear. Once his task was complete, Heracles returned Cerberus to the Underworld, where he resumed his eternal watch at the gates of Hades’ domain.

The Other Labors

While the Twelve Labors cemented Heracles’ status as a legendary hero, his exploits extended far beyond those mandated tasks. These additional adventures, known as the “Parerga,” showcase his unwavering courage, resourcefulness, and willingness to help those in need.

Achelous

Achelous, the mighty river god, ruled over the rushing waters of Aetolia in central Greece. Revered as the source of life-giving freshwater, Achelous was a powerful deity, often depicted as a strong bull or a man with a bull’s head.

One day, a contest arose for the hand of Deianeira, a beautiful Aetolian princess. Achelous found himself pitted against the formidable Heracles, a legendary hero known for his strength. A fierce wrestling match ensued, the earth trembling with each clash. During this epic struggle, Heracles, with his immense power, managed to snap off one of Achelous’ horns.

This wasn’t just any horn, however. It was a magical horn overflowing with abundance, a symbol of prosperity and nourishment. From this broken horn sprang the legendary Cornucopia, or Horn of Plenty, forever spilling forth fruits, flowers, and all manner of bounty.

Alcyoneus

Alcyoneus, a fearsome giant and king of Thrace, possessed an unusual advantage – immortality within the borders of his homeland, Pallene. This made him a formidable opponent, a fact Heracles, the legendary demigod, discovered during his travels.

One day, their paths crossed. Heracles, known for his cunning and strength, devised a strategy. He waited until Alcyoneus, lulled by a sense of false security, fell into a deep sleep. Seizing his opportunity, Heracles unleashed a volley of arrows, followed by a series of crushing blows from his mighty club. Though formidable, the wounded giant was no match for the hero’s relentless assault.

However, simply defeating Alcyoneus wasn’t enough. To ensure his demise, Heracles had to remove him from Pallene’s protective borders. With a mighty heave, he dragged the giant’s staggering form across the land. The moment they crossed the boundary, Alcyoneus’ immortality waned, and he succumbed to his wounds.

Legend tells us that Alcyoneus’ seven daughters, filled with grief, were forever transformed by the gods. They became a flock of kingfishers (alkyones in Greek), their mournful cries echoing through the land, a constant reminder of their fallen king.

Antaeus

Antaeus, a monstrous giant who roamed the Libyan sands, was a terror to travelers. Son of Gaia, the Earth Mother, he drew his strength from her very touch. Any unfortunate soul who crossed his path was forced into a wrestling match, doomed to be added to the grisly collection of skulls adorning the temple of his father, Poseidon.

Heracles, the legendary demigod known for his strength and cunning, arrived on the scene. As he faced Antaeus in the dusty arena, he noticed the giant seemed to grow stronger with every passing moment. Sensing something amiss, Heracles called upon Athena, the goddess of wisdom, for guidance. In a flash of insight, Athena revealed the source of Antaeus’ power – his connection to the earth.

Armed with this knowledge, Heracles shifted his strategy. He grappled with the giant, but instead of pinning him to the ground, he hoisted Antaeus high into the air, severing his contact with the earth. Suspended and weakened, Antaeus became vulnerable. Heracles, seizing his opportunity, delivered a crushing blow, finally vanquishing the monstrous giant.

The Caucasian Eagle

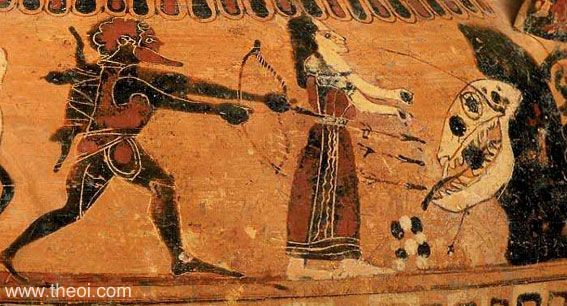

Prometheus, the Titan who dared to steal fire from the gods and gift it to mankind, was condemned to a horrific punishment. Bound in chains to a desolate peak of Mount Caucasus, he endured a relentless torture. A monstrous eagle, its wings blotting out the sun, was sent by Zeus himself. Every day, this cruel avian predator would descend and tear at Prometheus’s ever-regenerating liver, causing him unspeakable pain. Night after night, Prometheus’s liver would heal, only to be ravaged again at dawn.

Centuries passed, and Prometheus remained shackled, a symbol of both defiance and suffering. Then, Heracles, the mighty demigod, arrived, determined to free the Titan. In a display of courage and archery prowess, Heracles unleashed a volley of arrows that found their mark. The monstrous eagle screeched and fell, its reign of torment finally over. With the eagle vanquished, Heracles could finally break Prometheus’s chains, setting him free from his agonizing ordeal.

The Peloponnesian Centaurs

The centaurs, a rowdy and boisterous race with the bodies of men and the legs and instincts of horses, hailed from the wild mountains of Arcadia. Their reputation, however, was mixed. Some, like Pholus, were known for their hospitality. Others, fueled by a love of wine and a quick temper, were a constant threat.

Heracles, on his quest to retrieve the Erymanthian Boar, encountered a band of these unruly centaurs at the cave of his friend Pholus. Pholus, eager to honor a guest, opened a jar of divine wine, a gift meant to be shared carefully. The intoxicating aroma, however, attracted the other centaurs. Drunk on the fumes and fueled by their base desires, they stormed the cave, demanding the entire jar.

A brutal clash erupted – the Centauromachy. Heracles, ever the defender of order, fought back with his signature ferocity. He launched a volley of arrows tipped with the deadly Hydra’s venom, each one finding its mark. Many centaurs fell, their cries echoing through the cave. The few survivors, realizing their folly, fled south, some seeking refuge on the Malean peninsula, others welcomed by Poseidon himself in Eleusis.

Eurytion

Eurytion, a centaur hailing from the wild lands of Arcadia, wasn’t known for his noble spirit. He descended upon King Dexamenus of Olenos, demanding the hand of the king’s daughter, Deianeira. Fearful of the centaur’s strength, the king reluctantly agreed. However, on the day Eurytion arrived to claim his bride, a champion stood ready to protect Deianeira – Heracles, the legendary demigod.

As Eurytion approached with a boisterous entourage, Heracles, known for his unwavering courage, intervened. A tense standoff ensued. Eurytion, fueled by arrogance and a sense of entitlement, may have underestimated his opponent. A fierce battle erupted, though the details are lost to time. What remains clear is that Heracles’ strength and determination prevailed. The mighty centaur Eurytion was defeated, ensuring Deianeira’s safety.

Nessus

Nessus, a cunning centaur ostracized from his Thessalian kin, found refuge by the rushing Aetolian river Evenus. Here, he became a ferryman, capitalizing on the misfortune of travelers. When Heracles, the mighty demigod, arrived with his new bride Deianeira, Nessus saw an opportunity. Inflamed by Deianeira’s beauty, he attempted to take her captive.

Heracles’ enraged roar echoed through the valley as he unleashed a poison-tipped arrow, felling the centaur. Nessus, in his final moments, concocted a cruel deception. He offered Deianeira a supposed love charm – his own blood, tainted with the Hydra’s venom. Deianeira, fearing for her future, naively accepted the gift. This act of trust, fueled by a desperate love, would become a twisted weapon, turning Heracles’ own strength into his eventual downfall.

The Cercopes

The Cercopes, a pair of mischievous, monkey-like creatures, were notorious for their trickery. Plaguing the lands of Lydia with their antics, they specialized in stealing and swindling unsuspecting travelers. One day, their sticky fingers led them to the mighty Heracles, who was known for his strength and short temper.

As the story goes, the Cercopes pilfered Heracles’ weapons while he was peacefully resting. When the hero discovered his missing gear, his fury was palpable. However, upon finding the culprits, a peculiar sight greeted him. The Cercopes, dangling upside down from a pole Heracles had slung over his shoulder, were engaged in a hilarious display of acrobatics and witty insults. Their antics, a desperate attempt to appease the angry demigod, proved to be their saving grace.

Heracles, surprisingly, found himself roaring with laughter. Amused by their audacious display and undeniable wit, he decided to let them go unharmed. However, the Cercopes’ luck wouldn’t last forever. Legends diverge on their ultimate fate. Some tales claim they later angered Zeus, the king of gods, with their thievery and were transformed into monkeys as punishment. Others suggest they met a more permanent end, turned to stone by a vengeful deity.

The Trojan Cetus

A monstrous serpent, sent by the wrathful god Poseidon, coiled its way around the once-proud city of Troy. This sea-beast was punishment for King Laomedon’s arrogance. Laomedon, after enlisting Poseidon and Apollo to build Troy’s mighty walls, had refused to pay the promised reward. The enraged god unleashed the creature, its presence choking the city and poisoning the land.

An oracle’s pronouncements offered a grim solution – the sacrifice of a royal princess. Desperate, Laomedon chained his own daughter, Hesione, to the rocks, a living offering to appease Poseidon’s wrath.

Fate, however, intervened in the form of Heracles, the legendary demigod. Arriving at Troy, he learned of the city’s plight and Hesione’s tragic fate. A deal was struck – Heracles, renowned for his strength and courage, would slay the monstrous serpent in exchange for the magnificent horses King Laomedon had received from Zeus. Hesione’s life hung in the balance.

In a fierce battle, Heracles emerged victorious, the monstrous serpent slain. Yet, Laomedon, ever treacherous, reneged on his promise, refusing to hand over the horses. Heracles, fueled by betrayal, vowed revenge. He would return, and Troy would pay the price for the king’s deceit.

Years later, Heracles led a mighty assault on Troy. The once-impregnable walls, built by divine hands, crumbled before his rage. The city fell, sacked and plundered. Laomedon and his sons faced a bloody end, all except one – Podarces. This young prince, through quick thinking and a plea for mercy, managed to save his life. He offered Heracles a precious golden veil, a gift Hesione had made. This act of humility, a stark contrast to his father’s arrogance, earned Podarces not only his life but a new name – Priam, a king who would one day see Troy embroiled in a far greater conflict.

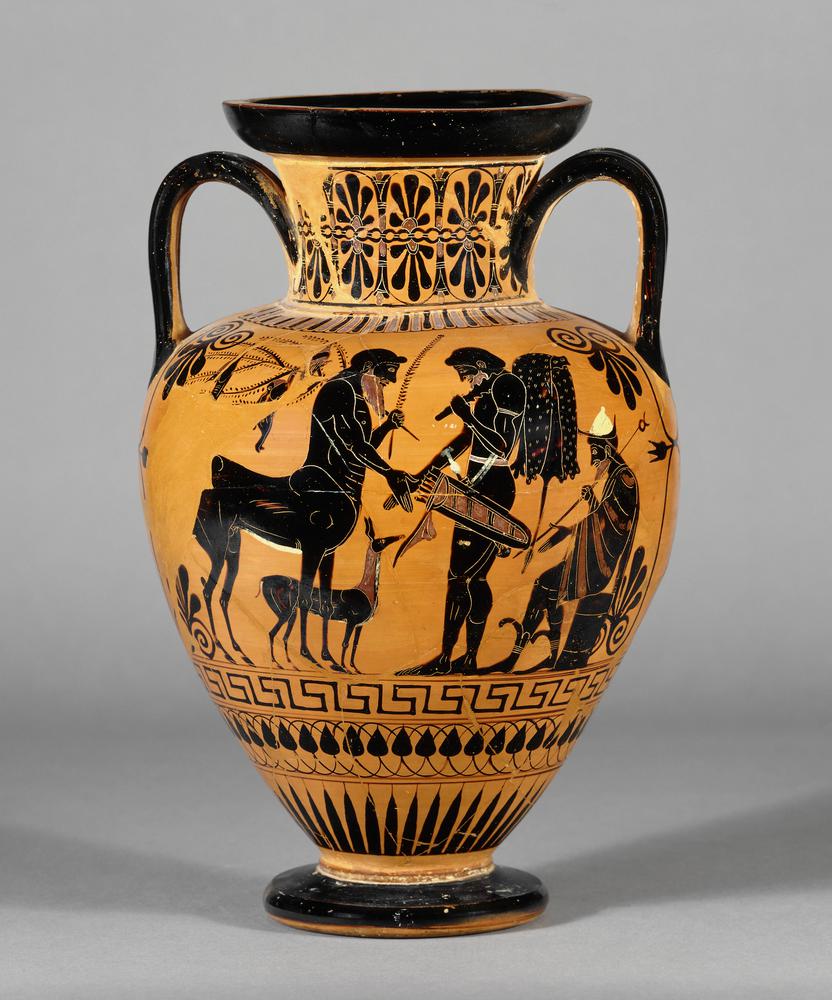

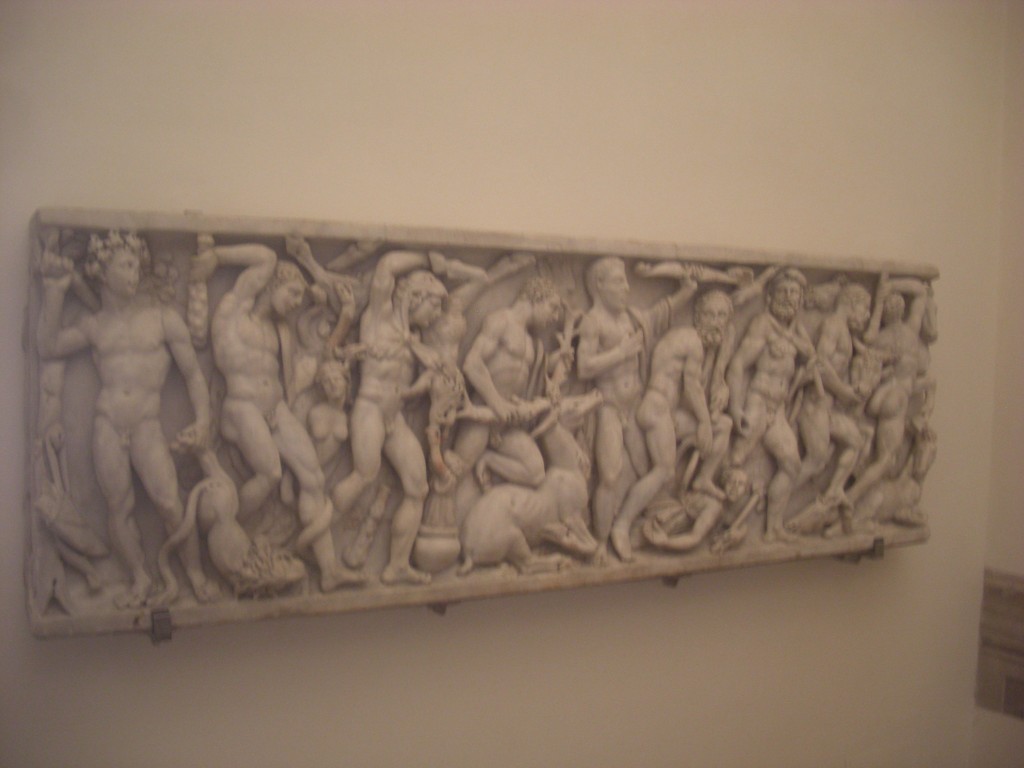

Art

Palazzo Altemps.